Blog

A Brief Overview of the Beginnings of High-Frequency Sound Strategies

21 November 2018 Wed

Esthetic research, which deals not only with the development of art but also with the hierarchies and value judgments that determine forms of current behavior, deals with conceptual analysis as well as concepts of cultural trends.

FATİH AYDOĞDU

fatih@amberplatform.org

By taking a short look at the history of technique and art in terms of understanding the relationship of art with the quotidian, we can further understand the relationships between science, technology, and narrative materials.

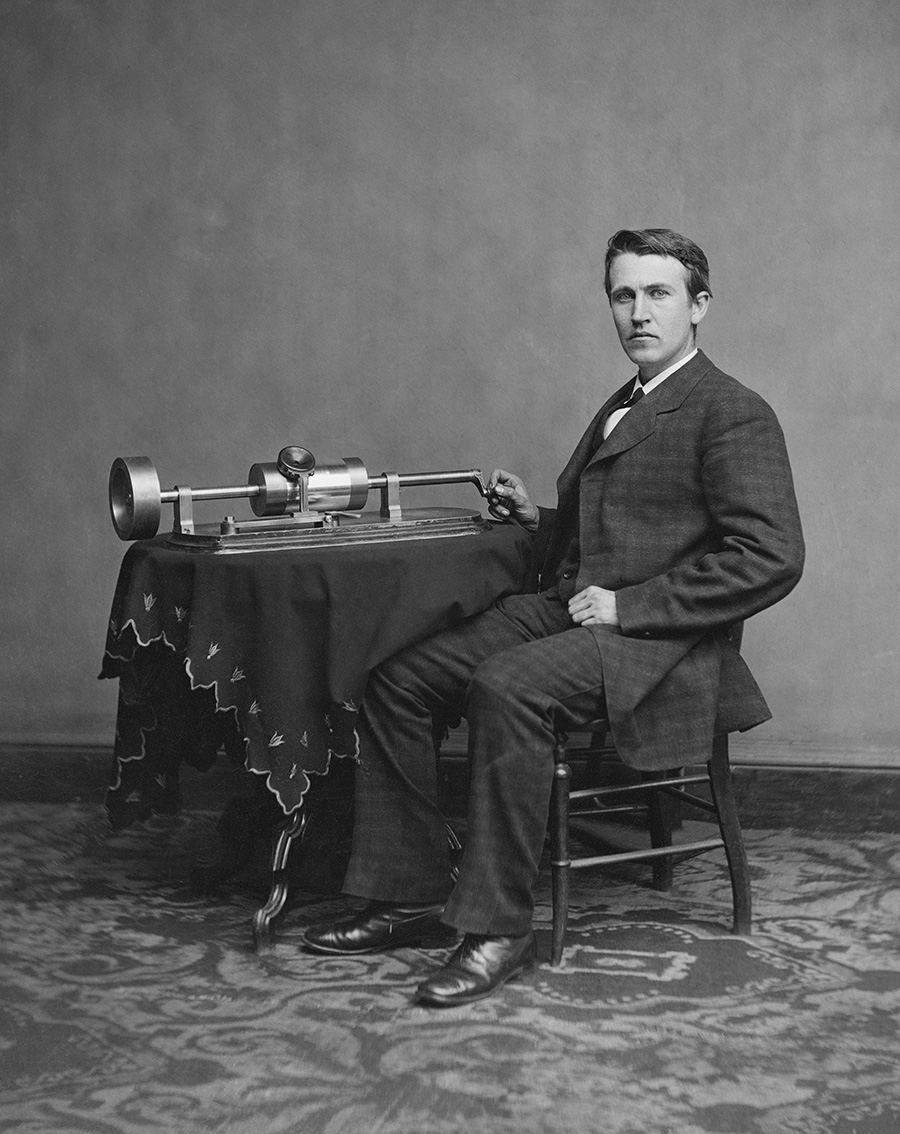

In the technical context, one of the most important inventions that led to the development of collective memory and archive is the recording machine called “Phonograph”, presented by Thomas Edison in 1877. [1] The possibility of recording and repeating sounds, cracked open the first door on the path to developing digital culture. The concept of “sampling”, which is one of the most popular concepts today and used in many different contexts from science to art, emerged as such.

But the story of modern art in the context of sound, and within this context, the beginning that leads to avant-garde subcultures and pop culture begins with another tone that has never been heard before: In 1913, the Futurist painter and composer Luigi Russolo [2] published the manifesto “L'arte dei rumori” [Art of Noise] on the sounds discovered in the major cities at the time. He also develops a series of instruments called intonarumori (sound generator) consisting of specially crafted surfaces to produce a variety of sounds and conical sound amplifiers. The Russolo photograph that stands in the middle of these vast speakers is his most recognizable image. Thus, for the first time in history, noise is embodied, and sound becomes an image.

In 1907, Ferruccio Busoni [3] wrote “Entwurf” [Sketch], where he talked about new sound scales, six-tone systems and the possibility of making sounds over electricity for the first time, and wrote about a new sound art esthetic. When this text was published in a revised version in 1916, it led to a heated debate. In 1917, Hans Pfitzner, a conservative, wrote a strong reply to Busoni with the text “Futurist danger”. The noise emancipated itself and became an equal composition material alongside the sound, the timbre and the silence. Edgard Varèse [4] would then prefer to talk about “organized sound” instead of music. In fact, during a lecture at Princeton University in 1959, "My fight for the liberation of sound and my right to make music with every kind of sound, has been interpreted as reducing the music of the past from power, even to reject it ... "The emancipation of sound is not to be understood as a reduction of music, but as a yearning to expand our musical alphabet," as he demanded in 1916 in the New York Morning Telegraph.

Sampling | Mix | Remix: Sound Art

As a mixed art form that art installation, performance, soundscape works, drama, poetry, sound / text art, radio art, film, and other easily categorized works that began to find their definition in the 1970s, sound art developed over time. Sound art is a category of art that is not tied to a specific period of time, geographic location, or group of artists and has not been named until the decade of its first works. While music is said to be related to time, it has been debated from the beginning that sound art is predominantly related to space. A sound work, like a visual artwork, does not have a specific timeline; It can also be experienced over a long/short period of time without a beginning, middle or ending points.

The focus on architecture, space and acoustics, which is common in the German “Klangkunst” tradition, produces works by highlighting experimental music paradigms in Anglo-American culture. Here, there is a hybridization of strategies available in both music and the visual arts. As in the case of visual arts, sound art tries to establish direct and intricate relationships with all kinds of elements [not only through the use of sounds, objects, lights, images, spaces, bodies].

Unlike electro-acoustic sound, the source of speech, brings into question with the resource for the sound and questioning the discourse, the narrative and the context in which sound exists. Here 'sampling', 'Mix', 'Remix' multi-channel placement take the place of collage and cutting techniques in the visual arts. In this context, the most widely used "Sampling" concept, symbolic and sub-categories form between Arts, Science, Economy and Ecology and the instruments specific to our language with various nuances are arranged, showing sharp brackets or stature as an expandable concept. Sampling, with its open-end definition, becomes one of the techniques that direct today's culture with conceptual, strategic, instrumental, esthetic, dynamic and fictional potential. As a production/research method, music, literature, genetics, communication, technique, psychology and network culture, while taking place in the common denominator, everything can be copied, diversified, manipulated, changeable in a digital era, the reality of the perception of reality as the main concept of the deconstruction. By re-collaging all kinds of archival materials as a means of creating new narratives, whether top and bottom linear chronological flow, musician and sound designer of the composition, science laboratories, bio-technology of gene engineering, news of the production channel, psychology, generates a new concept of virtuosity. Mix and Remix accompanying yourself with the method, as diversity and re-create endless material production, and has become one of today's Music Industry Arts indispensable tools for production.

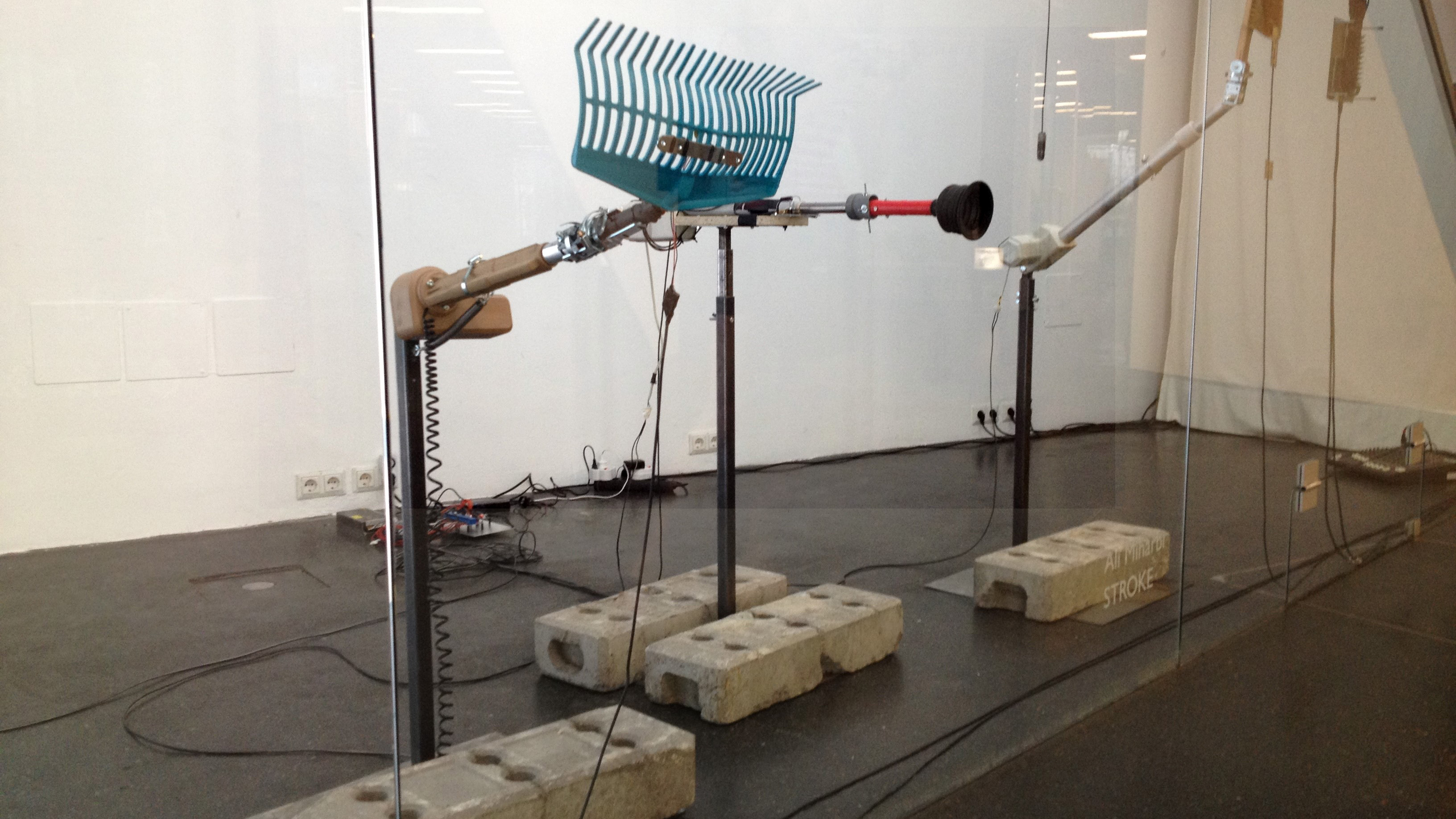

Sounds from the Homeland | Ali Miharbi

Sound Art, which has become more prevalent with the acceleration of technological development and the expansion of the means of production, or the use of sound in art more frequently, has started to find its place in our country. I can't list all the names as I would be concerned that I would be forgetting some people, but I could say that Ali Miharbi is one of the artists who produce critical works by working in the field of visual arts.

Our first collaboration with Ali Miharbi was in the 2011 Commons Tense / Commons Time exhibition at The Hague, the Netherlands in 2011 as part of the Today’s Art Festival, which we co-curated with Ekmel Ertan. His work Marked Territories was one of the most interesting and conceptual works of the exhibition. The main questions of the exhibition were: what are our common digital commons? What can we learn from Free-Software, copy-left movements, peer-to-peer systems, open source / open knowledge mentality, creative commons? Is there another economy and another ecology possible? How could art strategies be developed in this context? Miharbi, with the software he produced specifically, found the boundaries between the problematic neighboring countries on the images circulating on the Internet by analyzing them through the search engines and showed their prints in the exhibition. Joints included in the concept of the exhibition, copyleft, copyrights etc. concepts, such as the HBK-Saar exhibition in Germany, which is the second station of the exhibition. A lawyer from Berlin asked for a fee on one of Ali's prints in this exhibition on the grounds that his client claimed rights and threatened the artist and the organization with criminal sanctions. In such an artwork where the concept and the software are actually works of art rather than the printout, we were thus able to directly engage with the subjects that the exhibition wants to discuss.

Ali Miharbi, Stroke, 2014

Needless to say, Ali’s work and the following incident is a special example for us. Sharing, production, partnership, distribution, and the control society that we had foreseen to discuss in 2011, especially after September 11, have gone in a more and more negative direction since then. Orwell's transparent human nightmare for 1984, now turned into a daily reality through the digital network. By using free social media, we have been constantly monitoring our personal information, our camera, our microphone, and the normalization of personalized advertising. For now, the art community is one of the most questioning people and trying to develop the most effective counter-strategy.

Ali Miharbi has also been working with sound for a long time and producing objects based on the physical conditions, cultural context and use of language in sound. Some of these objects use objects that are uncontrollable through the inclusion of physical energy, such as breath-actuated objects. In his work Pneuma, Ali produces his work by giving shape, color and sound to the air - a whisper - which is constantly around us - and which we don't think much about. Here, air becomes a means of communication as a material that circulates, spreads, borders, contacts, whispers, transmits and guides. Miharbi, who deals with beliefs and theories in various contexts from Ancient Greece to Ottomans on the main concept of work, brings the randomness of the weather, the unpredictable and unpredictable energy of the wind and weather conditions into the art space by transforming it with the objects he makes. Using the wind direction information received through the machine, the machine in turn shapes his work and the natural wind to the viewer without exposing the wind whisper of the language is translated. Ali Miharbi, who produces vocals by following the wind in his work whisper, raises sounds from the acoustic vessels he produces based on the shapes the human throat speaks. With these similar noises sound like A, e, i, u, o; he warns us not to enter a part of the exhibition, emphasizing the power and danger of the material he uses. In the UK where he was invited to the Delfina Foundation for a residency, he takes his research a step further and works directly with the wind in the open field while producing his work, Wind Organ.

I would like to relay a part from the talk he gave at the Delfina Foundation here:

I became more and more interested in sound, not only because sound is directly perceivable as opposed to electric signals, but also because sound has many things in common with electricity, as both are used as media for symbolic communication, where sound becomes speech and electricity becomes electronics. As I am more interested in what sound does rather than the contents of the symbols it can carry, I started to explore its relationship with space. This includes sound installed across the exhibition space, as well as sound created in tangible ways, rather than being played through loudspeakers.

Endnotes:

[1] Thomas Edison; Phonograph | 1877

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phonograph

The Complete History of Sound Recording in three and a half minutes | Mr Audio >>>

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xo9d-kUsuS0

[2] Luigi Russolo | “The Art of Noises” | 1913

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luigi_Russolo

http://www.ubu.com/sound/russolo_l.html

http://www.ubu.com/historical/gb/russolo_noise.pdf

[3] Ferruccio Busoni

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferruccio_Busoni

[4] Edgard Varése

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgard_Var%C3%A8se

Delfina Foundation’s interview with Ali Miharbi

http://delfinafoundation.com/news/interview-ali-miharbi/

ABOUT THE WRITER

Fatih Aydoğdu (1963) studied at Mimar Sinan University in Istanbul and graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Aydoğdu, who continues his work in Vienna and İstanbul, is an artist, curator, sound and graphic designer. The artist focuses on media aesthetics, immigration and identity politics and linguistics in his works. Since 2011, he is a member of amberPlatform - Curatorial Advisory Board.