Blog

Close Reading Series IV –

Burak Bedenlier: Bystander

13 April 2021 Tue

This series of Close Readings emerged from a deficiency I observed both in contemporary art criticism and in my own writing practice: Although exhibition criticism, interviews, and monographic artist texts are produced regularly, focusing on a single work, interpreting, and analyzing that one work is a form we encounter less often.

In the Close Readings Series, I focus on the works from the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection, one at a time, and aim to produce texts on the works that I am curious about and want to further elaborate on. My expectation from these texts is that they are new and experimental, bring a fresh perspective to the work rather than to adorn it, and take both me and the reader to places we have never been to before.

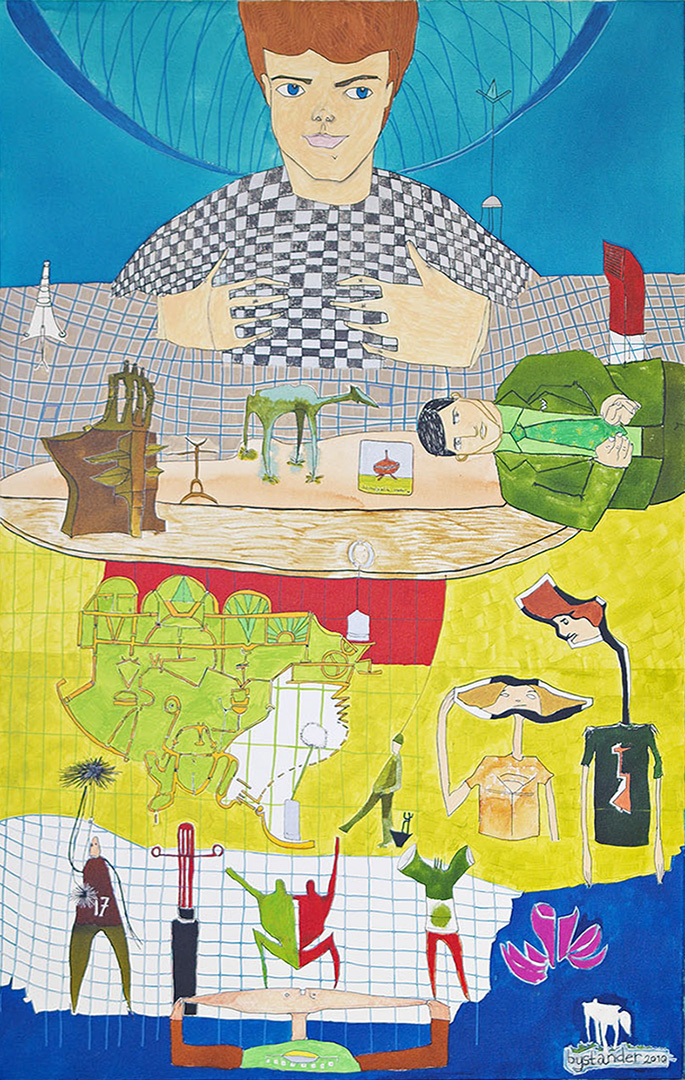

The reason why Burak Bedenlier’s work, Bystander got my attention has to do with its child-like 1 quality, which is something discernable in other works of the artist. This is a two-dimensional work, executed on canvas with mixed media. Although trained for sculpting, Bedenlier is an artist who also creates two-dimensional works.

Bystander has a dream-like, childish, instinctive essence. 150 cms in length and in width; painted in an elaborative style and with a rich narrative, the canvas seems to be divided in five horizontal zones. Bedenlier has composed this painting with the singular figures he has drawn between 2005-2018 in his notebooks of 14x9 cms that contained his drawings and studies. 2

Burak Bedenlier, Bystander, 2010.

Mixed media on canvas, 150x100 cm.

Installation view from Water Reverie exhibition.

It is possible to assert that the focal point of the painting is the figure that is at the top center of the canvas. We see him frontally from the torso up, yet there are many other figures in the picture. Elongated necks, narrow shoulders, amorphous heads… this stylization is what makes us ascribe the painting’s essence to childishness at first glance. We do know that 2 to 4 year-olds mostly draw mostly human figures after their “scribbling” stage. There is an affinity between their sketchy representations of human figures and Bystander: On the canvas, a figure is missing a hand; another one has only four fingers. The hands of the central figure recall the protagonist of Tim Burton’s movie, Scissor Hands.

The fact that the artist fills up the whole surface of the canvas is also similar to children’s drawings. Indeed, children tend to fill up the paper in order to represent the details they desire to reveal. The multi-perspective approach employed in depicting the elements of the picture; namely the combination of frontal, profile and bird’s-eye views, as well as a hierarchy of figures’ heights intensify the child-like construct of the painting.

Another quality of children’s drawings, “leveling” 3 is also found in Bedenlier’s painting. There is a card on a plane illustrated with a form that resembles a spaceship, under which is written: “ihtimalsizlik motoru” [improbability drive]. At first, I think that it might be a device about infinite probabilities, which exists in the phantasms of the artist. As I dig deeper, I find out that it’s from the book, Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and that it refers to a device situated on a spaceship called Heart of Gold, which is capable of turning infinitely probable events into reality. A device that is able to get the spaceship flip across stars and universes in mere seconds… I haven’t read the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, but it does not hinder me from entering the realm of this painting. Besides, there is an affinity between the construct of the device, which is based on imagination, and the abundance of probabilities examined in children’s drawings.

Burak Bedenlier, Bystander, 2010.

Mixed media on canvas, 150x100 cm.

Bedenlier’s striving towards this childish expression jibes with the modernist spirit of the 20th century. Let us remember the cliché that was brought up against nearly all pioneers of modernism at the outset of the 20th century: “Even a kid can do that.” The fact that children paint, not to show others and win their approval, but for their own sake has influenced many artists like Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Paul Klee (1870-1940) and Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985). In this context, it’s worth remembering the statement attributed to Picasso: “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.”

Children’s painting, which is an instinctive pursuit free from any concerns regarding color and form, indicates the absence of constructed academic rules, like the ratio and proportion or a central perspective. Due to its connection to the refusal of representation, it has gained momentum in the art and life of avant-garde artists of the 20th century. Artists including Paul Klee and Picasso had also taken an interest in their own paintings from their childhood years. The art historian Jonathan David Fineberg (1946- ) who presented significant studies in the field has unearthed the original children’s art collections that belonged to artists like Paul Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró (1893-1983), and thus broadened the field of research regarding these artists’ oeuvre with respect to their particular interest in the genre. 4

On a side note, I find it interesting that the figure at the focal point of the canvas – which I believe to be the self-portrait of the artist himself – is staring not at the viewers but towards somewhere outside with curiosity and attention.

The word “Bystander” is written on the lower right corner of the canvas. It’s translated to Turkish as “görgü tanığı” [witness], however this verbal adaptation does not fully correspond its meaning. Describing the term as “a person who sees an incident unfolding, but does not get involved and stands clear of it” is more explicative in the sociological context. It indicates a passive act of witnessing; the choice of not interfering when one is perfectly able to interfere. Referred as “bystander effect” in psychology, the phenomenon is explained as the obstructive impulse caused by the presence of other people to help a person in distress. 5

This title undoubtedly leads the way we interpret the work. When I ask the artist about it, he says: “As much as I find it unnecessary at times, if a title brings along the possibility of adding new meanings to a work, I opt for one. Although the title indicates a single figure among many others here, I gave it as a title to the work because it alludes to both the viewer’s position across the work and the fact that people merely bear witness to real incidents as a rule – not to mention, it puts me, the executant, in the position of a spectator. In other words, I stand over one side of the painting while the viewers stand over the other, and the painting between us becomes the medium of this witnessing.” 6

As I write this essay, women are subjected to violence in the streets and no one intervenes; it is announced on the official gazette one night, out of the blue, that Turkey withdraws from the Istanbul Convention, a treaty designed to protect women’s rights. As the burden of this passive witnessing gets heavier on my shoulders, it becomes inevitable to look at Burak Bedenlier’s Bystander and to contemplate it.

1- In literature, paintings with such qualities are referred as “naïve paintings” whereas their artists are referred as “naïve painters”, meaning they are usually not trained at academies but they are rather self-educated. However I prefer to use the adjective, “child-like” instead of naïve.

2- From the written correspondence with Burak Bedenlier, done on February 23, 2021.

3- İnci San, Sanatsal Yaratma, Çocukta Yaratıcılık, Ankara Tisa Matbaası, 1979.

4- Jonathan David Fineberg, When We Were Young: New Perspectives on the Art of the Child, University of California Publications, 2006.

5- Psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley have defined a behavioral pattern called “Bystander affect” for the first time in 1968, observed in emergency situations. Latané and Darley have developed this concept by examining the unresponsiveness of the people who had witnessed the murder of Kitty Genovese in New York, in 1964. Jamie L. Vernon, “Overcoming the Bystander Effect”, American Scientist, July-August 2016. https://www.americanscientist.org/article/overcoming-the-bystander-effect

6- From the written correspondence with Burak Bedenlier, done on February 23, 2021.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Nergis Abıyeva (1991) is an art historian, art critic and curator, based in Istanbul. Currently a PhD candidate at the Istanbul Technical University (İTÜ), Abıyeva graduated from Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University’s Art History department with the thesis “The Tracks of Dadaism on Surrealism” on the honor roll. During her undergratude studies, Abıyeva studied at the Brera Academy. She then graduated from the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University’s MA Program in Western and Contemporary Art with the master thesis, "The Art and Life of Tiraje Dikmen”. She won a Research Grant from SALT (İstanbul) with her research Tiraje Dikmen’s life and art in the context of Turkish artists who went to Paris in the 1950s. Abıyeva worked at Maçka Sanat Galerisi between 2015 and 2017 as an archivist for the 40th Year projects and contributed to the organization of the archive exhibitions. She is the assistant editor of the book, Görünmeyene Bakmak. Between 2017 and 2019, she worked at a private collection based out of Istanbul. Between April 2019-December 2020, she worked as a researcher at ARTER.

Her articles have appeared from 2015 onwards in periodicals including Sanat Dünyamız, Varlık, PRŌTOCOLLUM, Genç Sanat Dergisi, Istanbul Art News, Birikim and Argonotlar. She has curated the exhibitions, Kendiliğinden/Per se (Bilsart, 2020); Marvelous correspondences, subtle resemblences (Mixer, 2021). A member of AICA (International Association of Art Critics) Turkey since 2017, Abıyeva has been facilitating seminar programs and independent courses on modern and contemporary art since 2019.