Blog

Conversations: William Ewing

25 April 2019 Thu

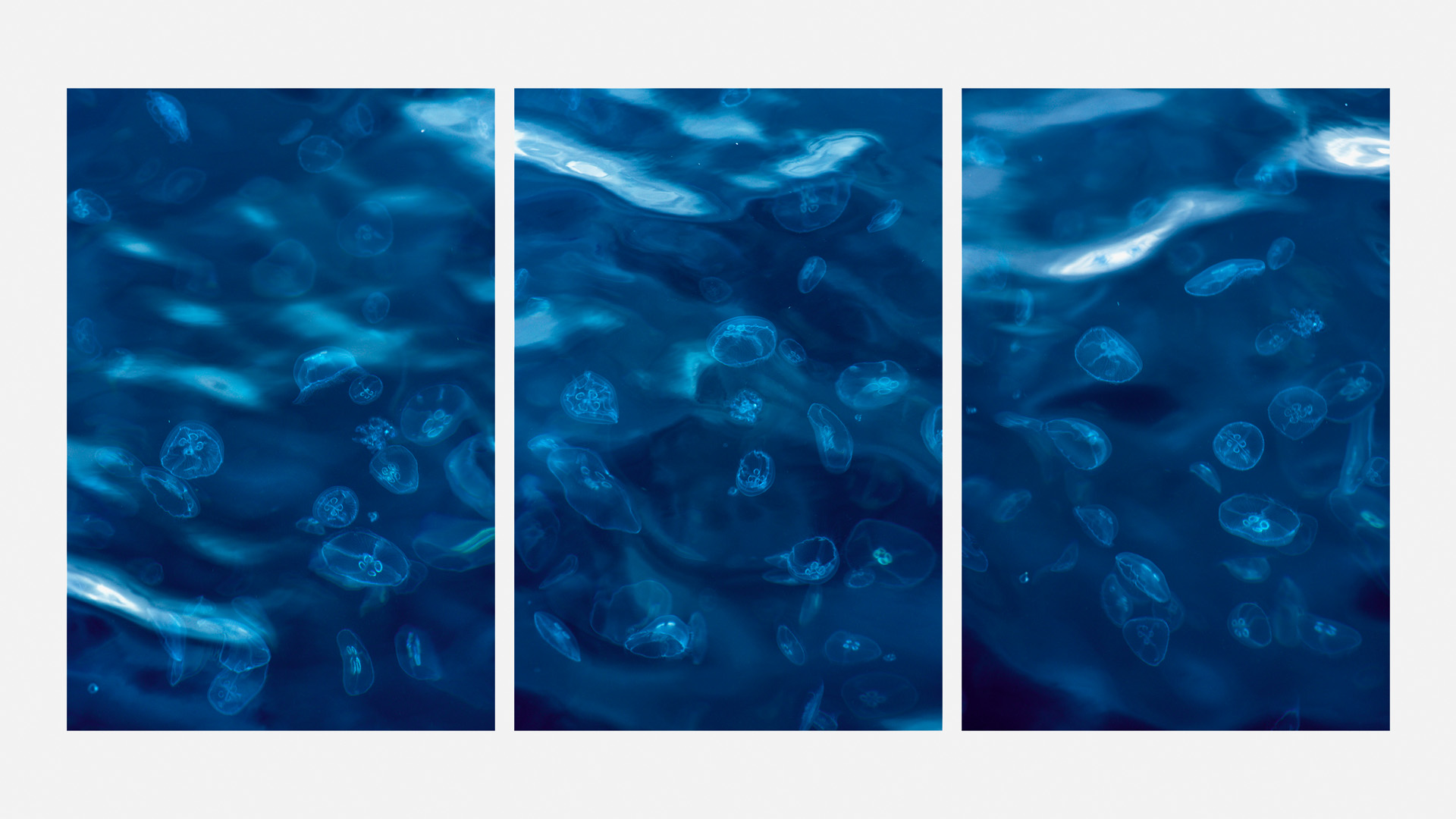

Guest curator of the exhibition Aqua Shock: Selections from the Water Project presented at Borusan Contemporary in 2016.

NAZ CUGUOĞLU

nazcuguoglu@gmail.com

Inviting a curator to an institution’s collection could mean various things: A dialogue or a monologue—emptying all the existing narratives to define them with new meanings or reshuffling them around. These collaborations require horizontal allies and generosity from both sides—an attempt to find the undercommons in a world of broken relationships.

Borusan Contemporary has invited seven curators in the last six years to its ever-growing collection of new media art to unlock these probabilities. This series of conversations is a curious response to this cultivating network of associations and relationships, marked with site-specificity and temporality, in a city that is always in flux.

– Naz Cuguoğlu

Naz Cuguoğlu: You curated Aqua Shock: Selections from the Water Project at Borusan Contemporary, focusing on the resource of water as one of the world's most pressing concerns. How was it for you to curate this exhibition at an institution situated next to Bosporus? There were two shows in Istanbul last year touching upon the politics of water, and its role in forming daily rituals and more importantly a way of thinking at Pera Museum and SALT Beyoglu, I am curious whether these politics affected your curatorial decisions.

William Ewing: Your reference to the Bosporus is intriguing, because I first saw the Bosporus in 1969, fifty years ago, and it had a great impact on me. At the time I knew something of its history, and this was part of the impact, but it was also very beautiful, very dramatic. I had taken the Orient Express from Paris, and it was before the era of the bridges, so it was a stunning sight, especially at night when it was covered with boats lit with lanterns. That’s all changed now. It’s a good reminder, on the one hand, that technology can triumph—the bridges are great accomplishments, with life-changing effects for many people—, but on the other hand, the fact that the water, which has never stopped flowing, has a new meaning: it’s no longer a barrier, an obstacle. Now we can think of it more abstractly, as a precious resource, easily squandered.

In those days there was no global consciousness of water, of course. It seemed limitless, like the air. Today this is different. Now I would think that anyone coming to see Ed’s show would be aware of water as a precious resource. Writing from Switzerland, when the glaciers are melting fast, I can assure you that water is an issue of great importance here.

But the curatorial decisions were not made in a direct relationship to Turkey’s situation. We chose imagery based not on specific subject matter—though we were conscious of the range of subjects covered—but on the power of the image. Ed’s work draws you in by this power, and then the questions arise: What is this? What does it mean? They are triggers.

Curating a show is very different from editing a magazine article. An editor will say: “We need this image because we need something from this part of Asia.” Or, “We need this one because it shows the use of water in desert farming.” But a curator of a show in an art context is free of those constraints: We choose the most powerful pictures. Then we sit back and we say: “Oh, this is interesting, the selection does show many aspects of the subject.”

NC: Did you get a chance to spend any time with the Borusan Contemporary Collection? Do you have any insights about the collection that you’d like to share? If you were a storyteller, what narrative would you make out of it for your listeners?

WE: I enjoyed immensely the other works on display, and thought they were installed with great sensitivity. I know several of the photographers—for example, I’ve worked with Otto Olaf Becker, and as a matter of fact both he and Ed are in my Civilization show. As is Massimo Vitali. And in the past, I’ve exhibited work by Lynn Davis and Michel Kenna. But Ola Kolehmainen’s work was a discovery for me!

A story? Well, I would do it visually. If you were to invite me to curate a show of the collection—total freedom—I would choose each piece like the word in a sentence, and construct a story in purely visual terms. I would start with one work, and then look for the next, and so on. The story would emerge, and I can guarantee that it would not be what I had imagined at the beginning!

NC: What made you drawn to photography as an expertise area in the realm of curatorial practice? What do you think about its relation to documentary, past, historical narrative-telling, subjectivity, and other curiosities?

WE: I was drawn into it overnight—literally—in 1972, when I discovered a beautiful empty gallery—a white cube—for rent in my hometown of Montreal. I jumped at the chance, and decided on photography as there was no such a place in the city at the time—and very few in the world. I knew nothing beforehand and learned on the job, making mistakes, correcting them, moving forward. Maybe better to admit, lurching forward!

I was always drawn to the aesthetics of picture making, and the documentary approach. I have never much liked set-up, fictional work, or conceptual photography, which frankly bores me. With so much of that work, you get the idea in a few images, and then the project goes on and on, across 100 pictures.

I came into photography before academia had laid its heavy hand on the medium. We see what comes out of art schools today, mostly earnest, socio-political work that can’t pass the test of true relevance. I was trained as an anthropologist, and I am always looking for this cultural relevance. I am not interested in flashes of fashion in photography—for example, gender, the body, identity, words uttered like mantras, with weak work to back them up. This will get the grants, of course, but I don’t believe it will have much staying power—with exceptions of course.

What I have always liked about photography, is that it’s always about something. One has to read and think. In the case of my work with Ed Burtynsky, for example, and let’s stay with water as a subject, I ended up reading and thinking a great deal about what’s evidently becoming a world crisis—even in Switzerland where I live, the glaciers are disappearing fast, with many implications. Still, the importance of the subject aside, my ultimate judge is my eye: Is the image potent, expressive, meaningful? Am I sucked into it? The subject can be important, but this does not mean the image is successful. The greatest disappointment for me is to see a great subject and a mediocre photographic treatment. Luckily there are enough successful pairings—relevant subject and good photographer—to keep me going.

You ask about curiosity. Yes, it often happens that I discover an image—it could be a fashion photograph, or an advertisement, that grabs me. Or something strange from the past. I do believe the past is an undiscovered country, largely. But there is not much curiosity about it. A curator trying to do something historical meets resistance. This is partly understandable, as we live in a time of great change and humans need artists as an antennae, to show the way. But forgetting the past too quickly leads us into peril.

NC: One of your most recent projects is “Civilization: The Way We Live Now,“ touring around the world to be shown in Seoul, Beijing, Melbourne and Montreal. You are interested in the knowledge of all the ironies and caveats this word excites. After curating this show, what does the 21st century look like to you? Can you tell us more about those ironies manifested in the works that you chose? What was surprising for you to discover in relation to ways we, humans, live now?

WE: Also, the show is going to Marseille’s Museum of Civilization, and the Auckland Art Gallery in New Zealand, and then to more western destinations, these latter ones in the planning stages.

It was a very personal choice, decided along with my co-curator Holly Roussell. “Civilization" is a pretty big word, so the show had to have weight to live up to it. But I expect anyone who sees it to question why this work was included, and that one wasn’t. We have 140 photographers in the show, which is both a lot and not many, given the thousands of very good ones working around the world. Obviously, we could add another one hundred. But we also wanted a show that would not exhaust the visitor, so we kept our ambitions on a tight leash. That being said, we feel we have touched upon many key issues of our time: urban mutation, shifting social relations, pollution, mass migration, leisure and escapism, war, protest, violence… But our show isn’t strictly documentary: We want powerful images to stimulate the viewer, excite their own imaginations.

I think of the show as a kind of bird’s eye view or satellite perspective: We look down on the field of photography and what do we see? Photographers everywhere! Documenting and interpreting everything! So, although photographers work alone mostly, we can also see photography today as a collective vision, a collective portrait of our times.

What does the 21st century look like to me, you ask? I am half pessimist, half optimist. Becoming 3/4 pessimist, I admit. The incompetence of our leaders, runaway science in the service of maximum, instant profits, pollution on a staggering scale, and of course climate change, and worse than that denial of climate change!

But I am functioning as a curator here, and my responsibility is to show what photographers are actually doing with these subjects, and other topics of great importance as well. We did not set out to make a critique of the 21st century civilization. Rather, we set out to show how photographers are dealing with the big issues. Some photographers have political opinions, and voice them, while others sit back and say: “No comment, I prefer to let my photographs talk!”

As for ironies, one visitor may see a statement of fact, while one may see an ironic comment. I was told by a journalist in Korea that the show seems pessimistic. Yes, maybe, but I think there is an optimistic side to it as well. Human beings have constructed an extraordinarily complex societal machine, i.e., civilization, which is planetary and incredibly complex—as the idiots who voted for Brexit are beginning to understand.

NC: How do you see the future of the photography in the curatorial realm in the age of Instagram? In one of your interviews you say: “You can now store 20,000 images on mobile phones! Everyone can become a museum.” How can future institutions find ways to reflect on this, what are some ways of camaraderie and gift economy—in the form of image sharing?

WE : I don’t think there is any doubt about the fact that we are living in a new visual world, ever sliding towards the virtual and irreal. There is a lot of feel-good talk about the positive aspects of sharing, but I see this with foreboding. What I do find interesting is how younger photographers crave old-form books and exhibitions. If you had asked the Edward Steichen in 1919 what was most important to him in getting his work recognized, he would have said “books, magazines and exhibitions”—what a young person would say a hundred years later!

But on the social media side, I do not see an increase in visual literacy. And the advertising and marketing people find ever new ways to lead us by the nose. Still, I benefit from this new world, and work within it, so I do feel conflicted—and even sometimes hypocritical.

For me an image of a screen lacks substance—and I mean metaphorically. Personally, I need to have a print on a wall, in a book, or best of all, in my hand. Then I can savor it. As for curating, I’m open to what comes my way, and I do make exciting discoveries, but I have to look at a lot of banal material—often by so-called big names—to get to it.

Every year I lead a brainstorming seminar in Umbria, and we try to imagine various futures of/for photography. Even though I define the future in three levels: the immediate future—the one we must all contend with now (i.e., the next 2 or 3 years); then the intermediate future—say the length of a house mortgage of educating your children, 30 years—; and then the speculative future, next 100 years. But we never get to that third level, and mostly we stay with the near future! Who among us can really, truly ‘plan’ for five years ahead? Curators, dealers, publishers… we’re all fumbling in the dark. As for the photographers, it must be an exciting time, but terrifying too. Where to go? What to do?

NC: You work a lot with the book format—thinking about your monographs on Erwin Blumenfeld, Ray Metzker, Leonard Freed, Arnold Newman, and your thematic books Out

of Focus; Lasting Impressions; The Body; The Face; Landmark: The Fields of Landscape Photography. How does the book as a form affect your way of curatorial thinking? When you turn an exhibition into a book, do you find it limiting to think within the 2D space of the book, or are there any liberating aspects for you, such as creating a different narrative, one that was not told in the form of the exhibition?

WE: I have always disliked straight catalogues. Useful often, but they never inspire me. I prefer to make stand-alone books. I see book and exhibition as complementary, two parts that make up a whole. I think of book and show as two pillars leaning against each other. Each needs the other.

Yes, 2D and 3D presentations are so different! I love the page, especially the double-page, and I love walls and corners. The same images are experienced so differently in each of them. In a book, I like the fact that you don’t know what’s coming as you turn the page. But visiting a show, you can walk in and grasp a good number of works in the space, so the surprise isn’t there. For that reason, I hate big open spaces, I prefer small rooms with three or four works maximum. then you can curate each room as a unit. And then surprise comes with the next room, and so on.

What I also love is installing the same show in different museums, and finding how different and fresh it is each time. The actual physical installation of a show is intensely pleasurable for me! I do not believe this can be done on a computer. It can be maybe sketched out on a screen, but you have to be in the space, and feel the space, before you hang. and you should hang each work separately, as the placement of one will influence the placement of the next—and I’m talking about one centimeter being important!

As for my books, I always layout everything myself, which image on which page, and what size, and in what order. I then give this to the designer, who incorporates the text, and maybe suggests slight changes in what I have put here or there. But I give the layout 95% ready to the designer. This is a great pleasure for me, and I would never give it up.

I find most photo books today to be the old equivalent of a box of prints—no artful sequencing, no intelligent flow. Most of them disappoint me. But then I see something great, occasionally, and am delighted!

Going back to your “different narrative” question—my Arnold Newman retrospective, travelling now, had a structure in the show which was not at all reflected in the structure of the book. The show structure would not work in the book, and vice versa. But I would still argue that they are complementary, like I said, two pillars of the same ‘building’.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Naz Cuguoğlu is a curator and art writer, based in San Francisco and Istanbul. She is the co-founder of Collective Çukurcuma. She held various positions at KADIST, The Wattis Institute, de Young Museum, SFMOMA Public Knowledge, Joan Mitchell Foundation, Zilberman Gallery, Maumau Art Residency, and Mixer. Her writings have been featured in SFMOMA Open Space, Art Asia Pacific, Hyperallergic, Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, M-est.org, and elsewhere. She received her BA in Psychology and MA in Social Psychology, both from Koç University, and another MA from California College of the Arts’ Curatorial Practice program. She has curated exhibitions internationally, at institutions such as the Wattis Institute (San Francisco), 15th Istanbul Biennial Public Program, Framer Framed (Amsterdam), Kunstraum Leipzig, Red Bull Art Around Istanbul, 5533 among many others. She co-edited three books: After Alexandria, the Flood (2015); Between Places (2016); and The Word for World is Forest (2020).