Blog

Remembering Our Physicality:

An Interview with Mika Tajima

9 February 2021 Tue

NAZ CUGUOĞLU

nazcuguoglu@gmail.com

NC: There were two works in the exhibition which were produced in close conversation with the city itself. This dialogue has an important role in your practice. Did you get a chance to visit Istanbul and how was your experience?

MT: Yes, I have been to Istanbul a few times for site visits and research leading up to my exhibition at the Borusan and previously for a show at Protocinema. As you mentioned, in my practice in general, I really think about the impact of geopolitical events that are happening that will change the way people perceive the work. The work can be a reflection of and evolving reaction to a moment in time. More generally speaking, I am interrogating the experiences of our bodies and lives in the built environment surrounding us and dictating our activities and shaping us. Architecture, design, and technology, infrastructures ostensibly under the directive to aid or be at service to us, have also been developed to change us and even work against us. It's a two-sided coin. As an example, much of recent digital technology is supposed to help us communicate more easily and faster, but convenience comes at a cost of our privacy and what is done with our data, which is now used to target our sense, desires and reasoning. When I visited Istanbul, it was kind of a moment where things were really changing in a kind of authoritarian way—freedom of expression was at risk.

NC: Your works, such as Meridian and Human Synth, reflect the collective mood of a population expressed on live Twitter feeds or interpret future human sentiments. What happens when these works travel to different localities? When you compare your data in different cities, is it commonalities or differences that you observe? What was the general mood in Istanbul? As the artist of the work, you have access to that knowledge, while we as the audience only observe what is there in front of our eyes.

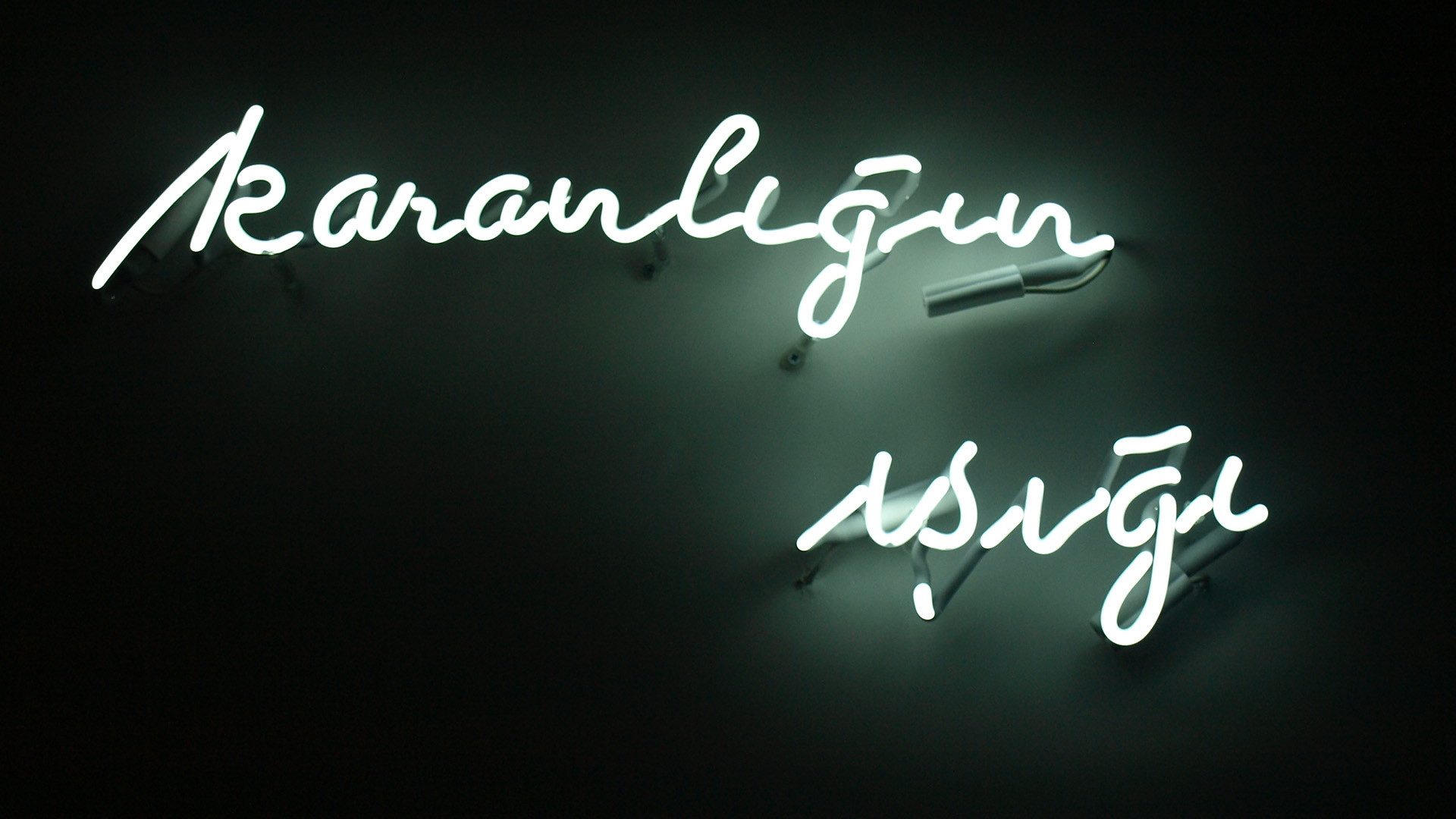

MT: For me, it's more about the absurdity and the poetics of trying to capture some collective energy or sentiment through a social media platform such as Twitter. In terms of interpreting the output specificities of Istanbul and comparing it to other locales, this also cannot be definitively ascertained since the data is so abstracted by transmuting it into another form (colored light or digital smoke) and is constantly evolving. These two particular projects, Meridian and Human Synth, question where our agency lies when the underlying technology aims to capture and understand who we are in order to control or influence us. Smoke and colored light become the metaphor for evading capture as both are constantly transforming and dissipating; they are simultaneously voluminous, present and ethereal. I really liked the title of that show, which was Æther or Esir in Turkish. There is a double meaning in that as it alludes to both escape and captivity .We are simultaneously contending with invisible forces of pressure through immaterial digital life while we still contend with physical coercion. In these projects, I contemplate this condition and seek the possibilities to navigate around these structures of control, oftentimes by misusing or breaking these very same technologies..

NC: Can you tell us more about how you landed on the title? Did you have any interesting research moments that led to that moment?

MT: Well, I was really lucky actually! Almost every object in the show was really about things that are immaterial—air, light, sound—materialized as an artwork. All of the works are sensorial experiences. I liked this idea of Æther, which is this mythical air of the Gods in Greek mythology. And they told me that its translation in Turkish, Esir, means being captive. It was such a great word play. It was by coincidence, but I loved it.

Mika Tajima, Social Chair, 2016.

NC: That’s such a beautiful coincidence! It was also hard not to look at your work from today’s perspective, such as Social Chair (2016)—at a time when we are all socially distanced, with more isolation and limitations imposed on our bodies. As your work is about technologies developed to control the human body, what kind of new ways of thinking did the current situation bring to your practice?

MT: What we're experiencing with all the social distancing, this rapid shift was already happening through digital technology. Now it's so extreme that you feel very disembodied from a lot of things. Still, it was something that has already been occurring with the rise of the information and digital economy and this whole way of working over email, or living through social media for instance. And before that, it was the corporate built environment that was trying to figure out how to make people work efficiently in an office space. Nowadays, a lot of people are working anywhere, at an airport lounge, at a café, or in transit somewhere. This situation puts the corporate architecture and design world in a crisis because they know that capitalism doesn’t need designated offices anymore. I was really struck by this whole system called “public office”— merging the notion of public space with the personal work environment. In this system, the foundational architectural element was the “social chair.” The irony is that you face outwards, even though collaboration and working together is the main idea of this system. And of course, now with social distancing, you almost don't even need a chair. People are on their bed or on the floor, walking around, etc. There is a real shift from needing furniture to help the body work more efficiently, to almost not even needing a body anymore. Now design and systems enter the psyche.

NC: Your exhibition was super sensorial and I think that's what makes the experience of art so unique, being around the artworks with our bodies, engaging in a dialogue with them. Now our bodies are not only longing for other human bodies, but also the physicality of the artworks. We are experiencing everything through our screens. Thinking about exhibition-making and your practice, what does this situation make you think in terms of the materiality?

MT: I am always thinking about that actually. And the exhibition in Istanbul in particular was all about the physicality of the body. Most of those works can't be experienced through a screen at all. The sound of the air, the air pressure blowing on your skin, the changes of the air pressure through the room—you can't feel those looking at an installation photo. Same with Meridian (2018), you can watch a video of it, but it's a totally different experience to be in that room. To experience your bodily response to that shift in the light color, you really have to be in the room. Different optics occur in your brain when the light color changes because your eyes will naturally start to adjust to the color temperature. At first when it shifts, the general mood of Istanbul is positive and it's going towards pink, you really experience it as a warm color. Then your eyes adjust and the pink turns to white because your brain wants to neutralize that color. And then it'll shift to green or another color , suddenly your brain has to readjust. You experience this massive change and realize: "Oh, something's happening right now in Istanbul, that's making this change." You sense that that something is happening. You might be alone in the room, but you are connected to a sort of communal experience of the city.

Mika Tajima, Pranayama, 2017.

NC: Since our bodies can't be in that room anymore, how does this situation affect your work and how it is experienced? All museums and art institutions are thinking about this shift already, as we all wait for things to go back to “normal.” How does your work transform when that sensual experience is not present anymore?

MT: Like you mentioned earlier, we have this longing to be around other bodies. What we are experiencing now is just an accelerated version of what was already happening. It's an extreme moment of disassociation and disembodiment. I'm working on future shows now, and it's really important for me that the works can be experienced in person as the works target our senses. There's a show coming up in London soon. Everything I do has a kind of expansiveness or volume in some kind of way, but some of these new works are actually very heavy, materially layered, solid objects. We need to remember the physicality of ourselves and that we're not digital material. This show was in development already before COVID-19 and it's the first show I'm having during this time. I want the show to contradict the need for just experiencing things virtually. Also, I'm working on another show which was delayed. There's a whole new series of work I'm developing, dealing with human energy and energy production itself using meditation as the metaphor.

NC: That sounds interesting, please tell us more!

MT: The exhibition is for Dazaifu Tenmangu, one of the oldest Shinto shrines in Japan. I will make a permanent artwork for their outdoor garden. This notion of permanent artwork is so beautiful at a site that has existed for over 1100 years. It gives me the opportunity to think of time in such an elastic way, as opposed to the digital, where time is extremely compressed and fast. These practices of preservation, permanence, evolution, life, and nature are all wrapped up into the Shinto practice. And meanwhile technologists are also trying to harvest human creativity and energy all the time, by monetizing all our digital labor and energy. Here at this shrine, that energy can be used for ourselves. One of the works I’m creating is a meditation platform. The object itself is referencing a hot tub spa bath, but it also looks like Mayan pyramids, or some kind of futuristic UFO. The works draw connections between the meditating human subject and the physics of material objects in relating to ideas of the “charged object”, higher energy states”, transitions”, and “substance”.

NC: This meditative aspect was also relevant for Æther. These works related to shamanistic practice of smoke reading, yogic practice of controlling the breath, or acupuncture. In a way, you were creating a thread between technology and alternative ways of healing.

MT: I'm really conscious of the new age, I'm both fascinated and critical of it. In our current climate, especially in Silicon Valley, self-care is so present, it's almost extreme. All of these kinds of new age practices for you to heal like veganism or fasting, they all become these regimens to regulate our bodies. For instance I reference “Pranayama” which is an ayurvedic practice to control the breath or to control the life force. I think that is exactly the mentality in technocapitalism.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Naz Cuguoğlu is a curator and art writer, based in San Francisco and Istanbul. She is the co-founder of Collective Çukurcuma. She held various positions at KADIST, The Wattis Institute, de Young Museum, SFMOMA Public Knowledge, Joan Mitchell Foundation, Zilberman Gallery, Maumau Art Residency, and Mixer. Her writings have been featured in SFMOMA Open Space, Art Asia Pacific, Hyperallergic, Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, M-est.org, and elsewhere. She received her BA in Psychology and MA in Social Psychology, both from Koç University, and another MA from California College of the Arts’ Curatorial Practice program. She has curated exhibitions internationally, at institutions such as the Wattis Institute (San Francisco), 15th Istanbul Biennial Public Program, Framer Framed (Amsterdam), Kunstraum Leipzig, Red Bull Art Around Istanbul, 5533 among many others. She co-edited three books: After Alexandria, the Flood (2015); Between Places (2016); and The Word for World is Forest (2020).