Blog

In Conversation with Edward Burtynsky: On Photography, Landscape, and Human Impact

19 January 2026 Mon

Asude Dilan Yiğit: Hi Ed, thanks for being here today. Let’s start with Erosion, which was commissioned by Borusan Contemporary Art Collection. Viewers are highly familiar with your photographs that showcase human intervention on the face of earth, especially those where the cause and effect of the Anthropocene are most apparent. The issue of erosion in Türkiye sits at an interesting intersection between soil degradation accelerated by climate change and the human efforts to combat it. How did you navigate this more ambiguous territory?

Edward Burtynsky: So, through the idea of approaching the project Erosion in Türkiye, I came to learn that Türkiye was one of the countries that had been doing a lot to overcome desertification and the effects of erosion. This is a large-scale terraforming project to reverse the effects of deforestation. Some of the images in the exhibition really point out the scale of this kind of terraforming, which is quite breathtaking. If you spend time with the mural in the exhibition, you can see that the terraforming happened probably 20-30 years ago. The grooves have disappeared, but you can see the lines of the trees are still starting to pop through. You can see that it has worked. It's still clinging on, but it's there and once the trees get big enough, they can then support life around them. Plant life can start to take off again, and then once you have your plant life then you have your animal life, you have your birds, you have your small animals, and they move things around and reseed things as well. So, this is really a kind of positive human activity to undo something that had a negative long-term effect by deforestation and probably over-farming combination causing the lands to dry out. It's an attempt to prevent that continued disintegration of that landscape.

ADY: Another aspect of your work is that there is never a definitive distinction between what is “good” or “bad,” that’s at least what I have observed through your own statements. You do not aim to showcase a solution that is “right,” but rather try to provide a space for the viewers to carve out their own perspective on the current state of the earth.

EB: Yeah, I've always done that. I’ve always placed my work within an aesthetic engagement with the subject, trying to find a moment where that subject becomes visually intriguing. That's what pulls you to the image. Furthermore, the pieces are revelatory, not accusatory. As humans, we're changing the ocean temperature and acidity of the ocean. We're changing the atmospheric CO2 components. We're changing the earth through terraforming, through agriculture, and through deforestation. And through building towns on wetlands, and all the other things that we do, we're changing natural habitat at a frightening speed. So, we are now the top predator, and the Erosion project reflects this understanding that we are the managers of our future and of what we are passing on to the next generation. These acts of reclamation are acts of hope. All of these are potentially there to see in the images that I create. The landscapes can tell these stories, and the work is bearing witness to that, and evidence that human activity can have a positive future effect.

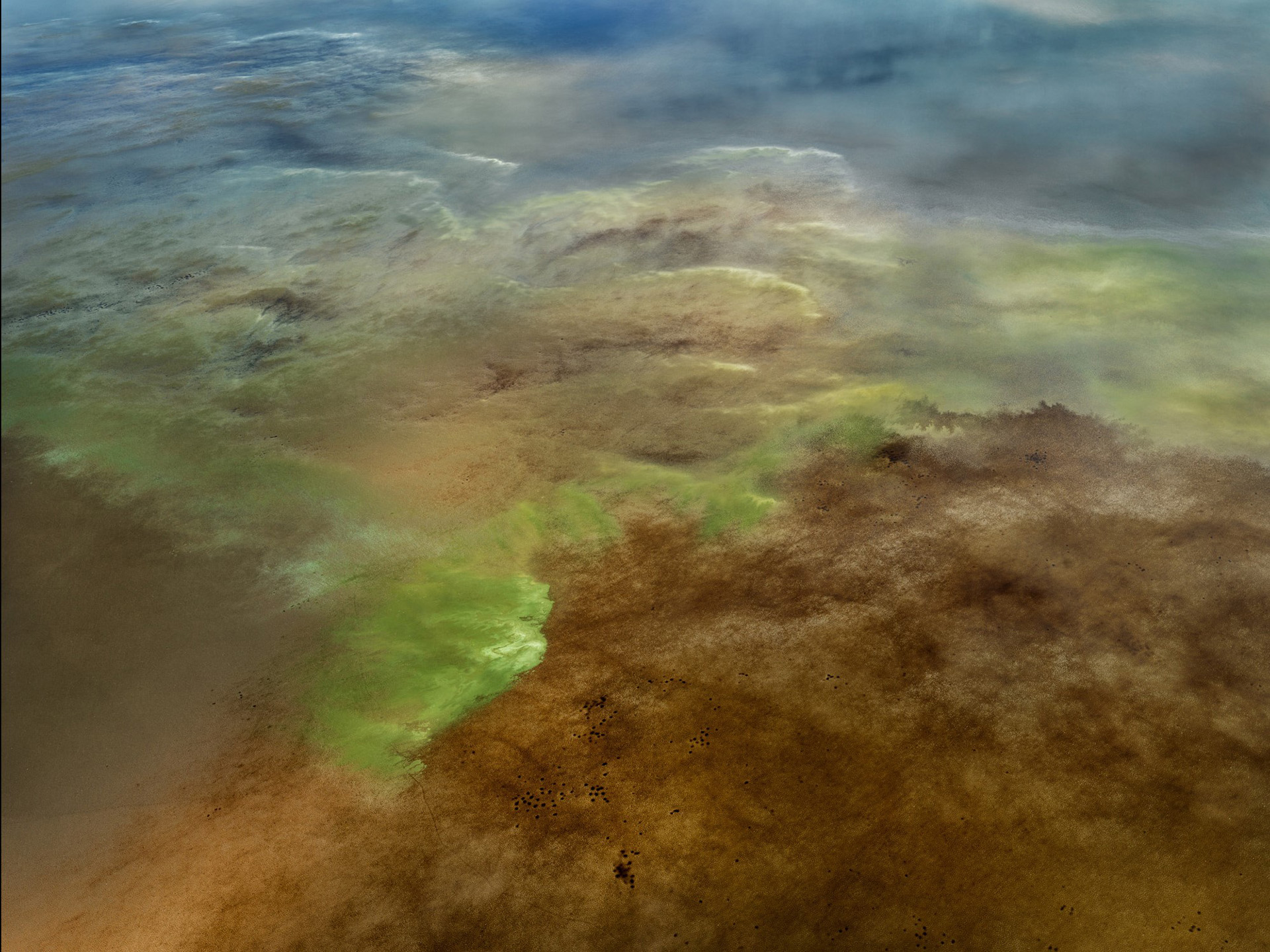

The mentioned mural Erosion Control #11, Burdur, Türkiye, 2022

Courtesy of the artist and Flowers Gallery, London

ADY: You’ve previously stated that you don’t see yourself primarily as an environmentalist, and that you avoid making work that becomes pure documentation. At the same time, you include enough information, so the images aren’t merely exercises in formalism. This fine balance between form and content is probably most apparent in the African Studies section of your solo show in Istanbul. How do you calibrate this balance?

EB: Well, I mean oftentimes when I talk about form and content, one of the things I've always tried to do is to not let either prevail. If form prevails, then it just becomes too simplistic, almost unidimensional. And if you let content prevail, then it very much moves into the direction of photojournalism. I'm more interested in neither of them having primacy; I want them to both sit on equal footing of form and content, so the work doesn't become too abstract or descriptive. When you bring these two together it’s not a fixed point anymore, it can go either way. I see it as a floating point. And, as long as the image is held within the context and it's not used as a propaganda tool, it serves as an inflection point for a deeper conversation to unpack about what it is that the image is describing. We've already passed the 1.5C global warming limit, and we're heading to 2C. I think it's more important than ever to have works that allow a healthy conversation on both sides of the aisle to talk about what's going on with our planet. When that storm comes and washes everything down, it doesn't matter if you're left, right, religious, non-religious, poor, rich. It doesn't matter.

An example of the artworks that are exhibited under “African Studies” at

Borusan Contemporary

Lake Logipi #1, Rift Valley, Kenya, 2017

Courtesy of the artist and Flowers Gallery, London

ADY: Exactly… You’ve been leveraging this aesthetic appeal of your images to draw the viewer in and prompt them to question the content for decades now. David Campany recently noted that your images allow several viewers to stand before them at once, and that this “social viewing” creates a dynamic with political potential. What do you think about this social viewing approach and its possible advantages?

EB: Yeah, it's true, in that multiple people can actually enjoy a piece at once and an exhibition allows for an audience. I think we pick up things from each other, and possibly, the way in which one person is investigating a photograph, looking and digging into it with their eyes, and noticing things, encourages another person to say: “Hey, what's that going on over there?” Additionally, with different distances you get different information from the prints. That’s always been something I've tried to do, invoke this double viewing. The piece first captures your attention because of the overall

composition, color, texture, light, feel, lines, etc. All of that could bring a cohesion to the image. And I also spend a lot of time making prints that satisfy as an experience through the detail: the sharpness, color, all of that… I would say almost all of my images can withstand the scrutiny of the six-inch stare. You can just shove your face 6 inches away and the image won’t fall apart. All the details will still be present, and you can read the characters, people, textures, industrial pieces, even an oil drum, a ladder, or whatever, they're all defined in there.

The exhibition is the space where you get that double viewing—in the presence of the artwork—and really feel it very differently because you're in relation to it bodily. You can walk up to it, you can stand back from it, you can explore its details through public viewing in front of the print itself.

ADY: Sure, and to have some other bodies next to me, knowing that we are all responsible for what we see in front of us, and realizing that only our collective actions can make a difference does add another layer to this experience. This togetherness renders an inevitable collective sensibility towards the subject we engage with.

EB: Yeah.

ADY: Next question is related to mining. The subject of mining became your first single-subject body of work, and we see some of your mining pieces at Borusan Contemporary show too. Subsequently, your most recent project is on mining of the rare earth elements that are used in technology. This is a thornier territory compared to fossil fuel consumption. How are you thinking about this recent work conceptually?

EB: Well, it's really a kind of a realization as an artist and a photographer going through a paradigm shift from a consumable medium of photography with film, silver, gelatins, chemicals, papers, and all of that to a durables technology, which is a light sensor with an optic that turns light into ones and zeros. From the ones and zeros you can transmit to other devices, and you can then also output back to a printer if you want to, or it can just stay in the digital zone where it’s only available on your phone or on your computer, or you can send it to somebody else and they can view it or post it on Instagram or whatsoever… In a way, we've dematerialized photography. There's been this transformation, this paradigm shift where now everything is digital. Looking at what we have to do in the world of energy: we have to stop using oil, coal, gas, and we have to go to solar, wind, nuclear fusion, geothermal, wave technology, etc. Anything, but burning fossil fuels… And all of the above are durables. Durables are battery technology, requiring rare earths for magnets for kinetic energy, copper and aluminum for the transmission, steel for building motors, etc. Whether we like it or not, and whether you think you know mining is environmentally friendly or bad, the alternative is worse. So, call it the lesser of the two evils. There isn't a simple right or wrong, and in my work, I try to embrace this complexity. There isn't a simple “Just do this and it's going to be fine.” Like I said, it's all of the above; it's not just one technology that's going to get us out of this predicament.

Uralkali Potash Mine #2, Berezniki, Russia, 2017

Courtesy of the artist and Flowers Gallery, London

ADY: That paradigm shift is unfortunately taking a long time to reach its full capacity. You also tackled this issue in the three feature films you co-produced. How does the moving image add new dimensions to your work? In what ways does it allow you to communicate what an exhibition alone cannot fully convey?

EB: With the first one, Manufactured Landscapes, it was a bit about following my practice, going into the world, and trying to unpack what is going on. Even the opening narration is me speaking about how damaging nature is damaging ourselves. The films were about respecting nature, believing in the value of nature in itself. Making sure that we respect what a tree does as being a tree, not as a building material…

I think by the third film, ANTHROPOCENE: The Human Epoch, there was an urgency that was really not as present in the other two films. If you listen and watch it carefully, it says that we're the cause of the next extinction event, the 6th great extinction, and we're having the equivalent effect as the asteroid that hit the earth.

ADY: Yes, the urgency is definitely felt heavily in ANTHROPOCENE. This time I’m moving from films to books. Photobooks are another medium that you’re keen on. You have built a remarkable canon of photobooks over decades with Steidl, and in 2016 you founded the Burtynsky Grant to support emerging Canadian photographers working on photobooks. What does the book offer, both to you as an established artist and to the next generation of lens-based artists, that other formats, such as exhibitions or digital platforms, cannot?

EB: Yeah, I've been a big believer in the book format. With an exhibition, it comes up and it goes down. Whereas the books, they give you the fuller context of the sets of ideas that you're working with. The writings provide you a way into the work and other ways to think about the work itself. I think it's a way to allow the work to continue into the future in a cohesive contextual way. Currently, I'm redoing all my classic books with Steidl because they're almost all sold out. So, that will be something to look forward to in the coming year, especially for people who don’t have a copy yet. My first book, Manufactured Landscapes, was printed in 2003 and it marked my trajectory as an artist. I witnessed how effective a book was to get my work out into the world, which is why I continue to include books as part of all my major projects now.

ADY: The book is also an archival piece that you reflect upon, that you go back to revisit your stance as an artist.

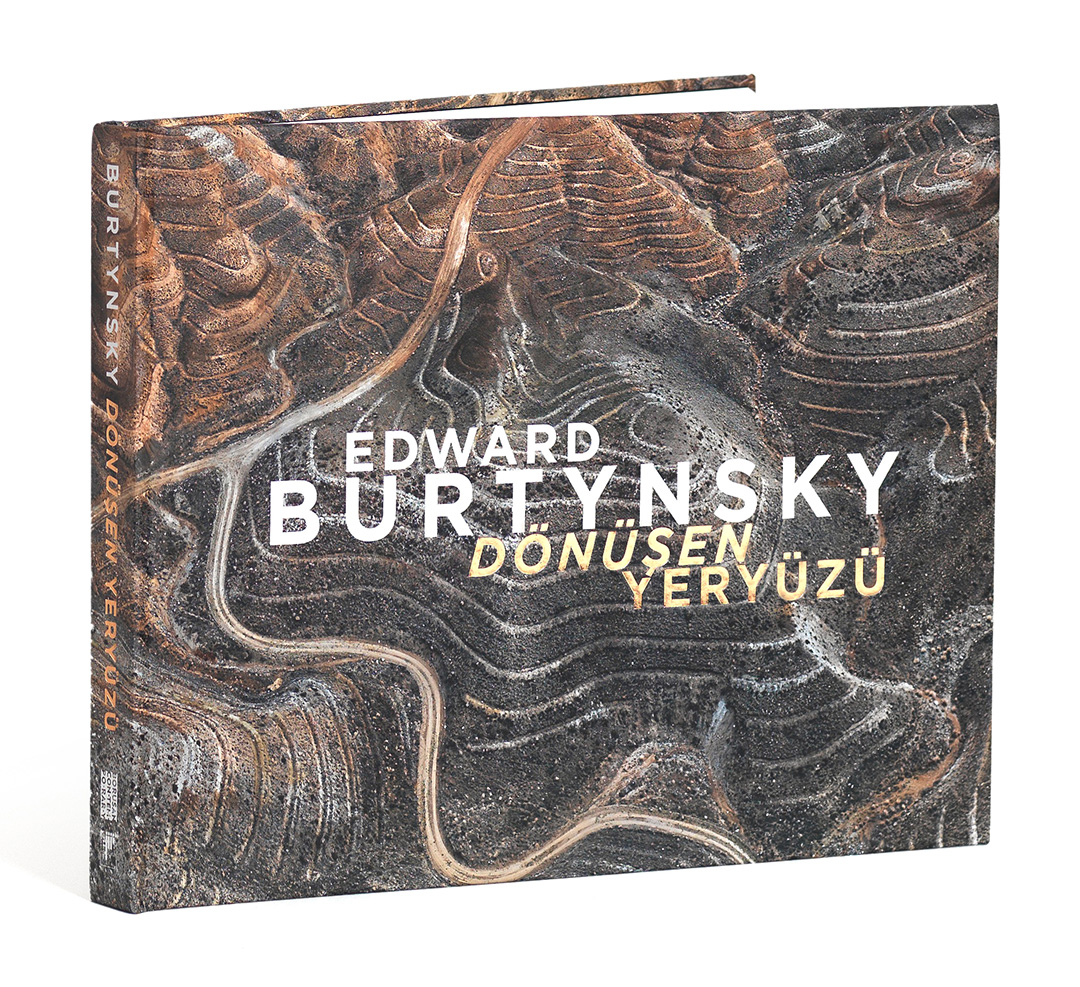

Edward Burtynsky’s Shifting Topography catalogue published by Borusan Contemporary

Photo: Hadiye Cangökçe

EB: Yeah. It’s a great tool to contextualize the whole project. It gives you a holistic outlook to your work. For instance, the Water project went on for 5 years. Oil, I studied it for 10 years to understand where it comes from, how it gets processed, where it goes and how it changed our world and what it's doing. So, all these things really open you up to a broad set of ideas and realities that you experience in the making of the work itself, by viscerally and kinetically being in the presence of it all. I’m trying to transmit that understanding through the works, through the films, and through the books, so that anybody following that train of thought will really understand the breadth of exploration and contemplation on how we as humans have changed and are changing the planet.

ADY: It is like a web of words and visuals where the reader can find their way through one point to the other. Lastly, I would like to touch upon COP30 in Brazil. So, unfortunately, once more, we failed to phase out the usage of fossil fuels. Nothing progressive came out of this COP and the nation-states who benefit the most from these fuels are still holding onto this power.

EB: It is a little disheartening because we're already running out of time. Politics and big money have a way to control the narrative, and they're unfortunately doing so to the detriment of all humanity and all life on the planet. Younger generations are going to be looking back at us and saying: “What happened when you had a chance to do something?” What's our answer going to be? In my own way, I did try.

ADY: For more than 40 years now.

EB: Yeah, I don't know if that clears my conscience, but at least I tried. I'm trying to stay hopeful. I've recently done this return to the natural landscape, which I refer to as a “Tribute to Nature.” The natural world is still here, nature is indeed resilient and can rebound. We have all the tools to solve the problem at hand. We just need to deploy them. As a society, we have the power. I'm trying to be in front of people and say there are reasons we shouldn't give up and we should continue, and I encourage other artists who want to speak, use their talents to try and tell these stories. There's a lot of room in here for a lot of foot soldiers to help shape consciousness that ultimately moves to action. But if you're not conscious of a problem, then you're never going to act on it.

ADY: That’s right. Thank you so much for this interview, I’m sure our readers will truly enjoy this conversation.

EB: All right, no problem. I hope so.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Asude Dilan Yiğit holds a transdisciplinary academic background that spans politics, architecture, and contemporary art across institutions including Middle East Technical University (Türkiye), Sciences Po (France), and Goldsmiths, University of London (United Kingdom). Her professional focus lies at the intersection of cultural analysis, institutional practice, and social transformation through the exploration of power structures and the possibilities of change across scales. Since 2021, Yiğit has worked across multiple cultural institutions in Istanbul, and she currently serves as the Assistant Curator at Borusan Contemporary.