Blog

Conversations: Christiane Paul

14 October 2019 Mon

Guest curator of “What lies beneath” presented at Borusan Contemporary in 2015.

NAZ CUGUOĞLU

nazcuguoglu@gmail.com

Inviting a curator to an institution’s collection could mean various things: A dialogue or a monologue—emptying all the existing narratives to define them with new meanings or reshuffling them around. These collaborations require horizontal allies and generosity from both sides—an attempt to find the undercommons in a world of broken relationships.

Borusan Contemporary has invited seven curators in the last six years to its ever-growing collection of new media art to unlock these probabilities. This series of conversations is a curious response to this cultivating network of associations and relationships, marked with site-specificity and temporality, in a city that is always in flux.

– Naz Cuguoğlu

Naz Cuguoğlu: What were the factors that made you curate the exhibition “What Lies Beneath” for Borusan Contemporary? Could you talk about the exhibition’s conceptual background, dealing with issues around disconnected realities and alienation?

Christiane Paul: When I started working on the exhibition in 2014, the world was entering a period of great instability and conflict. Migration escalated and officially became a crisis, economic inequality continued to grow, violent conflicts driven by clashes of religious and ethnic identities were erupting everywhere, and pro-democracy movements were ongoing. The Gezi Park Protests had happened in Istanbul in 2013 and there was a sense of political shifts.

Given all the sociopolitical upheaval, it would have felt strange to me to curate a mainly aesthetically and formally oriented exhibition, which runs the risk of appearing out of touch with reality. The atmosphere at the time was one of uncertainty. People’s trust in political systems seemed to be decaying and the complexities of all the political and economic forces at play were often hard to understand, which produced a sense of alienation.

I decided to focus the exhibition on the experience of these underlying forces and conditions beneath the visible surface that produce insecurities. My goal was to select works that capture these elements without being very literal.

NC: So, the sociopolitical factors underlining “what lies beneath” are an important conceptual background of the exhibition. What role do sociopolitical issues such as immigration and displacement play for these works’ narratives?

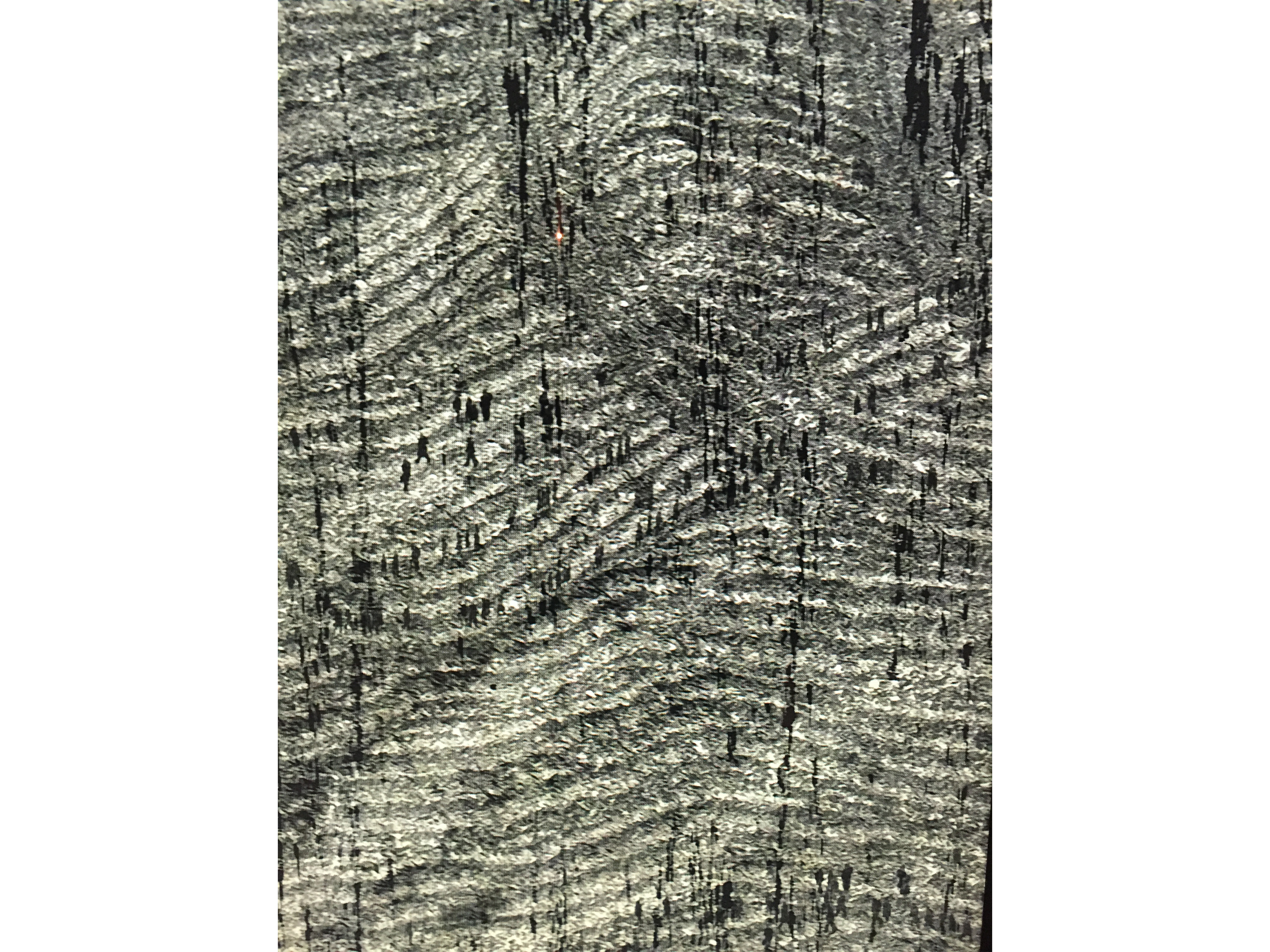

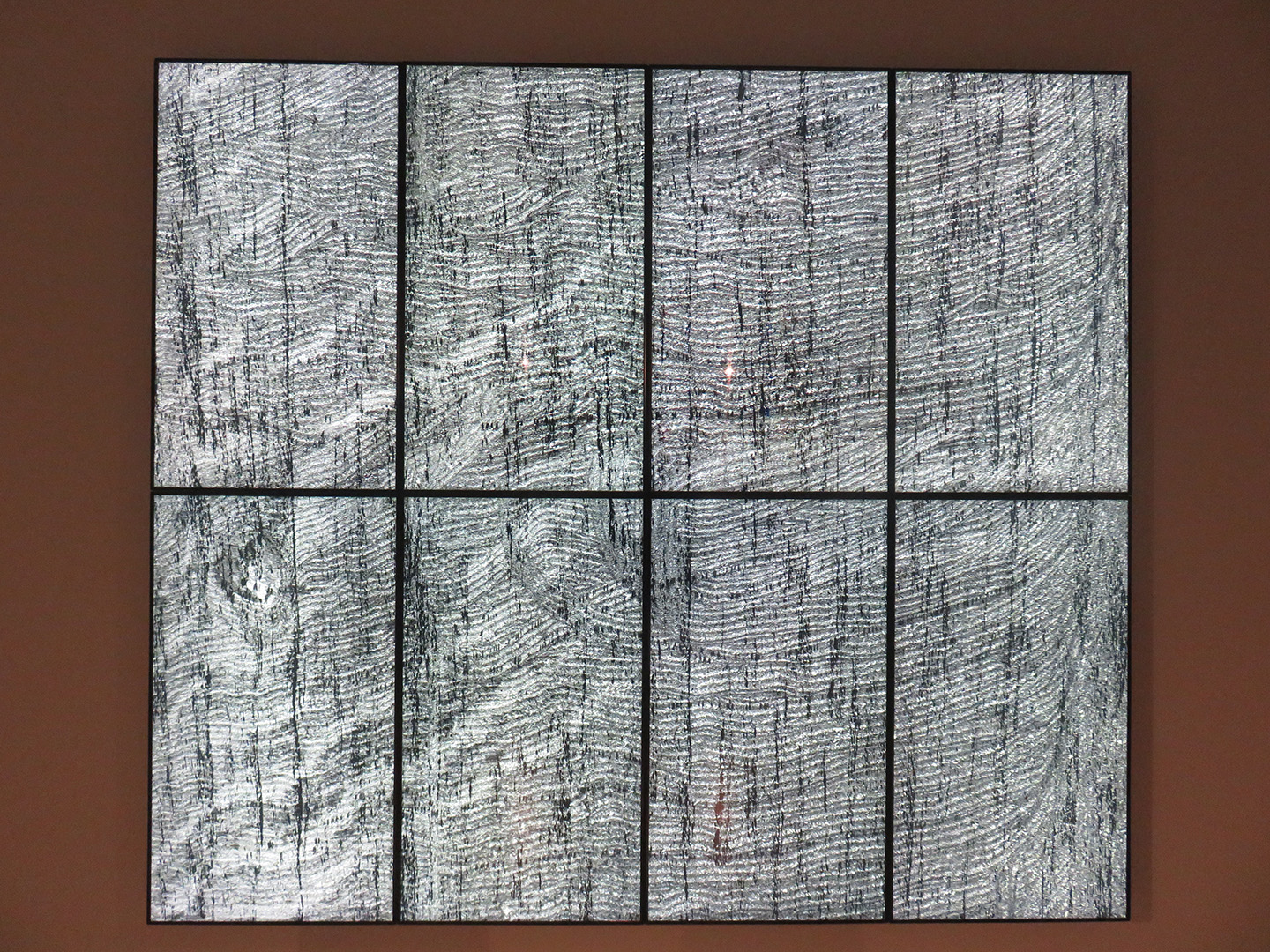

CP: Krzysztof Wodiczko’s video projection Guests explicitly addresses immigration and displacement by featuring the stories of immigrants residing in Poland and Italy that originally came from countries ranging from Chechnya to Sri Lanka and Morocco. The work communicates the ambiguous status of these immigrants’ existence, which entails both visibility and invisibility. Michal Rovner’s works shown in What Lies Beneath feature tiny human figures in perpetual motion, making their way through abstracted landscapes or circulating on the surface of a broken stone. While the pieces address a range of complex issues they also suggest a process of migration and imply displacement in the rupture of space that is created through the broken stone.

Overall the projects maintain a certain ambiguity and invite you to think about the conditions of humanity, invisible forces, and our fear of otherness. They all provide an opportunity to engage with aspects of the unknown.

NC: The three room-size installations in the exhibition were set up as an immersive storytelling experience for the viewers. Could you talk about this decision? How did you decide which rooms to include, and in relation to which works?

CP: The installations in the three gallery spaces functioned as a more abstract form of “storytelling” in that they weren’t conventional narratives, but still connected around the theme of the show. The choice of the rooms for each of the works was not only driven by the exhibition concept and the attempt to create contemplative spaces for emotionally responding to invisible forces, but also by very practical choices. Wodiczko's Guests consists of a dark space with projected windows that give a slightly blurry view of immigrants talking about the challenges of finding jobs and gaining legal status. It was crucial to have a more rectangular space that would allow to both project a certain number of these windows and let visitors position themselves in the environment, so that they would both perceive the “otherness” of the immigrants and see themselves as an “other” separated from them. The room needed to communicate the idea of the guest, stranger, or outsider on various levels.

Practical concerns also were involved in choosing the space for Michal Rovner’s works, which comprised a projection onto stone and several screens — all of them showing tiny human figures that function as 'human marks' and become a hieroglyphic text reflecting on relationships between time and space and the human condition. The human figures aren’t a conventional text but they nevertheless tell a story about temporality. Rovner's Broken Time (2009), which consists of two slabs of lime stone onto which the figures were projected, was so heavy that the stones couldn’t go into the elevator and we had to lift them in by crane over the balcony. There also was only one place in the gallery where the work could be placed because it had to sit on one of the structural supporting beams in the floor.

The artist Zimoun’s site-specific installation of 240 tall, standing cardboard boxes were “prepared” with dc-motors so that they would move and shake driven by ominous forces and create a sound architecture seemed to work best in an airy white space. They were placed in the semi-open space closest to the entrance. Experientially they also created a nice contrast to the darker gallery with Michal Rovner’s work and resonated with the movement of the chains of human figures.

NC: Did the building of Borusan Contemporary play a role in these decisions — either in relation to its intimate closeness to Bosphorus or its odd architecture resembling a haunted house?

CP: The building did not play a role in the conceptual framework for the exhibition itself — meaning, I did not choose projects for the building per se — but it certainly was a perfect site for the exhibition and supported the concept in subtle ways. Migration, which was a prominent theme in the exhibition, relies on borders between countries and the identities of nation states. Istanbul to me is an amazing place in that it is a threshold between Europe and Asia, a site of intersections between continents, religions, and cultures. This by nature implies tensions, whether they are immediately visible or not, and those were at the heart of the exhibition. Tensions may often be difficult to understand in all their complexities, which creates apprehension and maybe even feelings of being “haunted” by all the historical baggage. A “haunted” house by the Bosphorus — the dividing line running through a transcontinental city — seems the perfect place for this exhibition.

NC: How do your roles at The New School and at the Whitney Museum of American Art feed each other? (from a pedagogical perspective or from an interdisciplinary perspective)

CP: I feel very fortunate and privileged to work in different capacities that complement each other and create a perfect feedback loop. My curatorial work at the Whitney (and beyond) has been the basis of my writings and research on curating digital art and also informs my teaching. I am able to work on a practical and theoretical level in parallel, which keeps me grounded, and also allows me to provide my students with “real world” experience. Naturally my research in turn also informs my curatorial concepts. Right now I’m also holding the positions of director and chief curator of The New School’s Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, which comprises the university’s two galleries. My experience of curating within an institution such as the Whitney has been tremendously helpful in overseeing the exhibition program of The New School galleries, which by nature is more tied to curriculum and learning.

NC: What are you working on these days?

CP: Right now I’m working on a few upcoming online commissions, which will launch on the Whitney Museum’s artport website over the course of the next year. I am also curating an exhibition on art and artificial intelligence — with the working title The Question of Intelligence – AI and the Future of Humanity — which will open at the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Gallery of The New School next year. The show will give an historical and conceptual overview of the ways in which digital art has critically engaged with different areas of development in AI. The artworks will explore the automation of the senses and the impact of AI on societies with respect to surveillance, labor, and knowledge production, as well as AI's potential for creativity and artistic creation.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Naz Cuguoğlu is a curator and art writer, based in San Francisco and Istanbul. She is the co-founder of Collective Çukurcuma. She held various positions at KADIST, The Wattis Institute, de Young Museum, SFMOMA Public Knowledge, Joan Mitchell Foundation, Zilberman Gallery, Maumau Art Residency, and Mixer. Her writings have been featured in SFMOMA Open Space, Art Asia Pacific, Hyperallergic, Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, M-est.org, and elsewhere. She received her BA in Psychology and MA in Social Psychology, both from Koç University, and another MA from California College of the Arts’ Curatorial Practice program. She has curated exhibitions internationally, at institutions such as the Wattis Institute (San Francisco), 15th Istanbul Biennial Public Program, Framer Framed (Amsterdam), Kunstraum Leipzig, Red Bull Art Around Istanbul, 5533 among many others. She co-edited three books: After Alexandria, the Flood (2015); Between Places (2016); and The Word for World is Forest (2020).