Blog

On Shifting Temporalities

31 October 2019 Thu

An Interview with Kira Perov on Bill Viola’s Creative Processes.

MERVE ÜNSAL

merve.unsal@gmail.com

On the occasion of Bill Viola’s Impermanence at Borusan Contemporary, we meet with Kira Perov, Viola’s wife and the executive director of Bill Viola Studio. Perov has also curated, organized and coordinated Viola’s exhibitions around the world. We delved into the history of the medium of video art, thinking about the medium’s evolution in the last half century through Viola’s practice.

For Deniz Can’s interview with Perov, discussing the artist’s creative process, please see here.

Merve Ünsal: Bill Viola is recognized as a pioneer in the field of moving image. I'd like to ask what that position of being a pioneer has meant, as I'm sure there were challenges to gaining acceptance using forms and methods that were not perhaps readily accepted as artistic media at the time?

Kira Perov: There were so many new art forms emerging and developing in the late 60s and the early 70s. Acceptance of these happened very slowly. But it was a very exciting time and artists were eager to experiment with these forms, especially action, or performance art, very often recorded with video. It took a long time for these forms to be accepted as art by museums. So artists and interested curators created a new forum for video, the video festival, often attached to film festivals. This stimulated the growth of the medium and much work was being produced together with people to champion this new art form. For example, it was hard to ignore video art when Wulf Herzogenrath curated the media section for the documenta in 1977. This was a groundbreaking exhibition with artists such as Nam June Paik, Wulf Vostell, Bruce Nauman, and Bill Viola. He showed an installation from 1976, He Weeps for You. It was the first time he presented a work on such an international scale. He had shown earlier in the 70s, but this was the first time he was getting such international recognition. By this time artists were experimenting with video as three dimensional work, not just videotape pieces. These latter were often passed by in group shows because as a viewer, these works were often lengthy and were shown on a monitor, a box, and to sit for some time to watch them was very difficult to do for casual visitors.

Gradually video art become more accepted by the general public. I remember in 1983, John Hanhardt who was the media curator for the Whitney Museum (New York) commissioned a new piece from Bill, Theater of Memory for the Whitney Biennial. This was the first time a video was shown on the same floor, together with paintings and sculptures in such a venue. We had shown in other venues, but this exhibition was something new for us. There were other institutions that developed video programs, such as the San Francisco MOMA and the Long Beach Museum of Art. LBMA had a media arts center, which was quite unusual for any museum—it was a place where artists could produce and post-produce their works. Since they kept a copy of all the pieces they produced, LBMA ended up with something like 4,000 tapes in their collection, a very interesting statement of the times. It includes local, regional, national and international artists. This collection has now been restored and is being migrated and preserved into the digital realm, and is housed in the Getty archives.

MÜ: It sounds like institutions reacted differently and their responses changed over time?

KP: Very differently. Barbara London, long time video curator at MoMA in New York, for example, was able to maintain a program for showing video for over 25 years. Of course, she was not able to command any kind of real gallery space for a long time. She often used what was called a project space, which was for new works and new artists. It was on the way to the rest rooms, of course, and we joked that this is where video works were always located in museums. We showed the work He Weeps for You there in 1979, the same work that was in documenta in 1977. In 1987 an exhibition with Barbara was finally presented in the main galleries that included three major installations and a program of videotapes that screened in the auditorium. Since MoMA is such an important institution in the world of museums, for the medium of video this was quite a critical moment.

MÜ: You have mentioned in an interview that there were times when technology had not caught up with what Viola wanted to do. Could you give an example of such a case? When did technology catch up?

KP: Right from the beginning Bill was interested in working with slow motion. That was really difficult to do in the early 70s. His first experiments were with reel-to-reel videotape that he was slowing down, manually moving the tape itself. In 1976, he created a group of works called Four Songs, one of which is Truth through Mass Individuation. It was commissioned by a broadcast network in New York. Their equipment allowed Bill to develop his slow motion techniques on a drum system, the only way to achieve slow motion then. This piece is all about the dissolution and disintegration of the image. One section was recorded on Wall Street at 5 in the morning. He carries a rifle that he shoots once into the air, he then walks closer to the camera and shoots the gun again. Each time he shoots the gun the video and sound are slowed down more and more and you can see and hear the reverberations getting slower and deeper as he moves closer to the camera. It was a very cumbersome process but now it’s very interesting to watch what he was able to do back then. In another section he uses a symbol that he drops it to the ground in very slow motion and you can hear the sound slowing down too in a deep rumble. We always recorded the image with the sound for the early works, until the end of the 90s. In 1992, Bill needed to slow an action down much more, and we decided to use a special 35mm film camera that we rented in Hollywood that could shoot 300 frames a second. With so many frames, when you slow it down, the slow motion is really smooth and beautiful. Most of the Passions series pieces were recorded that way between 1999 and 2002. Shooting time was about 60 seconds, and that translated to 10 minutes of slow motion time.

MÜ: Viola's practice encompasses many traditions from across the world, both in form and in content. How did he arrive at this mode of working? What does it mean for him to be working with historic and traditional materials?

KP: The history of image-making starts with Paleolithic times, and the thread is passed on through all of human history. Everybody has the tendency to be creative but creativity must be nurtured to be developed. Bill’s wide ranging reading of various ancient mystic texts from Islam to Buddhism to Christianity and our extensive travels have greatly influenced the work. He has also spent a lot of time looking at images created by the great masters from the east as well as from the west, and understood that all artists are influenced by those who came before. Today we call the statue of Buddha an artwork, but the word “art” probably wasn’t even in part of the vocabulary when it was made. I believe that all art, including contemporary art, needs to have a function.

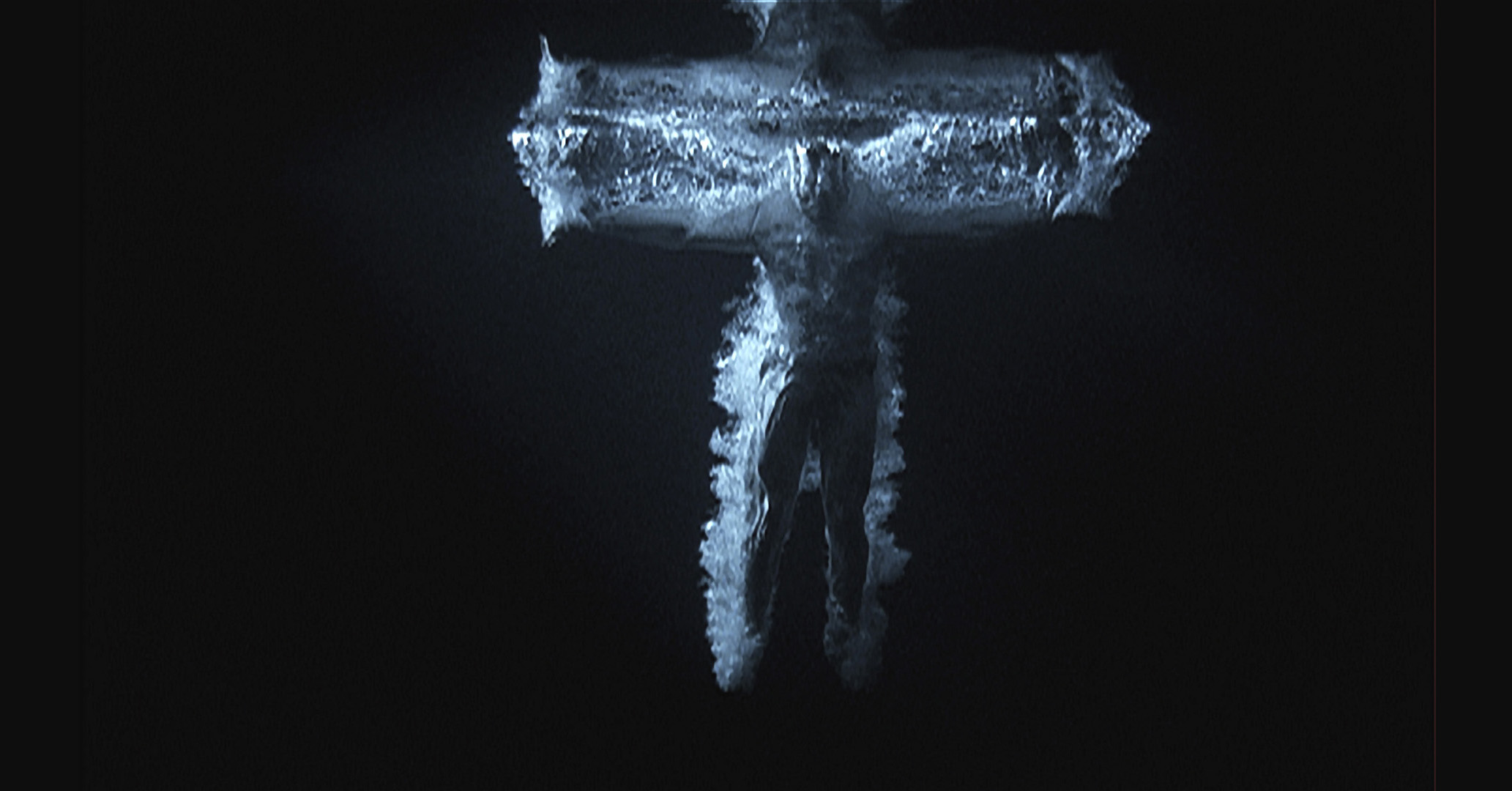

Bill Viola, The Encounter, 2012.

Color high-definition video on flat panel display.

© Courtesy Bill Viola Studio.

MÜ: The slowing down of time is very present in the works and I can also see how this slowing down also works as a methodology.

KP: Some scientists say that time does not exist. It’s just a figment of our imagination. People have been measuring time for thousands of years but only relatively recently were clocks synchronized in different countries to accommodate train schedules in Europe. The Industrial Revolution played a big part in making large groups of people be precisely on time for something. I recently read somewhere an anecdote about a researcher watching a shaman going into a trance and they were skeptical. An older woman commented, “There are some things you can’t see. Can you see Tuesday?” So that’s what you grapple with. You can’t even think about timing literally, you just know that some things need to be slower and you feel you need to slow things down in a specific way. Each piece has its own rhythm. Bill wanted the Passions series pieces to be very slow in order to examine the subtle nuances of the expression of the emotions. There is one work, Anima, 2000, which is 80 minutes long! A triptych, it is a portrait of three people, one man and two women, who go through a series of emotions within a recording time of 60 seconds. Shot with the high-speed film camera, normally this could be stretched to 10 minutes. However, Bill worked closely with an editor, to slow each portrait down so much that you seem to be looking at three photographs. It’s the feeling of knowing that the clock’s hand is moving, but you can’t see it.

Bill Viola

Bill Viola was born in New York in 1951 and graduated from Syracuse University in 1973. A seminal figure in the field of video art, he has been creating installations, films, sound environments, flat panel video pieces and works for concerts, opera and sacred spaces for over four decades. Viola represented the US at the Venice Biennale in 1995. Other key solo exhibitions include: Bill Viola: A 25-Year Survey, The Whitney Museum of American Art (1997); The Passions, J. Paul Getty Museum (2003); Bill Viola – Visions, ARoS, Aarhus (2005); Hatsu-Yume (First Dream), Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2006); Bill Viola, visioni interiori, Palazzo delle Esposizioni (2008); Bill Viola, Grand Palais, Paris (2014); Bill Viola. Electronic Renaissance, Palazzo Strozzi, Florence; Bill Viola. Installations, Deichtorhallen, Hamburg; Bill Viola. Retrospective, Guggenheim Bilbao; and Bill Viola: Selected Work 1977-2014, Redtory Museum of Contemporary Art, Guangzhou, China (all 2017) ); Bill Viola: Visions of Time, SESC (Social Service of Commerce), São Paulo, Brazil (2018); and Bill Viola / Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (2019).

In 2004, Viola created a four-hour long video for Peter Sellars’ production of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde that has had many performances in the US, Canada, Europe and Japan. Viola has received numerous awards including XXI Catalonia International Prize (2009), the Praemium Imperiale from the Japan Art Association (2011), and was elected as an Honorary member to the Royal Academy, London in 2017.

Kira Perov

Kira Perov is Executive Director of Bill Viola Studio. She has worked closely with Bill Viola since 1979, managing, creatively guiding and assisting with the production of his video works and installations. She edits all Bill Viola publications and organizes and coordinates exhibitions of the work worldwide. Kira Perov earned her BA (Honors) in languages and literature from Melbourne University, Australia in 1973.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Merve Ünsal is a visual artist based in Istanbul. In her work, she employs text and photography, extending both beyond their form. Ünsal is the founding editor of the artist-driven online publishing initiative m-est.org.