Blog

Landscape Distancing

15 June 2020 Mon

The COVID-19 crisis altered our relationship with landscapes. In many cases the only landscapes we enjoyed this spring were the ones our windows showed.

Alleyways, fields, mountains and squares outside our neighborhoods became accessible solely via cameras. Around the time infections peaked in April, BBC filmed landmarks of world capitals using drones. The abandonment and silence of these panoramas chilled and enchanted. Without humans, landscapes appeared calmer, cleaner, and a great deal curiouser.

In her works the Dutch photographer Ellen Kooi ponders deserted landscapes. Her images often conceal a person, an object, an idea behind a scenery, and raise questions about how we relate to our surroundings. Her models are mostly solitary figures—young adults immersed in nature in deep meditation—and Kooi situates them against barren Dutch fields. She excels at capturing brooks, meadows and trees under fog or during daybreak. In her work nature reenacts turmoils of figures who take refuge in its many domains. A girl on a tree stump gazes the city that lies ahead in Velsen Lampen (2008). Velsen, a province in North Holland, illuminates her, as if spotlights controlled from its streets have captured this fugitive during an attempted escape. A shadowland between Velsen and the meadow in the front reminds the angst and uncertainty of crossings.

In the merging of these figures and landscapes, painting traditions of the Dutch Golden Age resurface. Kooi’s scenography pays tribute to Jacon van Ruisdael’s chilly mountain pine forests and Hendrick Avercamp’s winter scenes surveilling city crowds. Like those masters she observes landscapes from a safe distance that eventually alters the scenery. A detail in a field, potentially appalling, disappears in a choreography that beautifies all surfaces. But Kooi’s use of distance also creates suspense. Schoten’s(2014) Ophelia-like figure swims under the water, but she might as well be a drifting corpse. The image, a nature morte in the tradition of Millais’ Ophelia (1852), glows with life and hints at death. It may be a crime scene: mystery and suspicion of foul play encircle the image’s inception.

Ellen Kooi, Velsen-Slootmist, 2003.

97 x 174,5 cm. Fuji Crystal archive print, diasec dibond.

Kooi lives in Haarlem. A 25-minute train ride away from Amsterdam’s Central Station, her hometown would make an excellent locale for a crime drama. In Kooi’s work, locals choreographed to a tee constitute a narrative that shares the ambitions of Balzac’s comédie humaine of provincial life. Familiar figures and sights populate these depictions of Haarlem and nearby towns: the beloved lake near Kooi’s home and the fields she wanders for meditation reappear in various panoramas.

But the tranquility of Haarlem inspires unease and makes a fitting subject for an aesthetics of suspense. In Sirjansland-meuwen (2009), a woman stands in the way of seagulls; the town, hidden behind mists, both embodies and restrains her desires. She appears liberated, but may in fact be ostracised and on the run. These figures, however tangentially, recall the ugly history of Dutch collaboration, particularly of small provinces, under the rule of Reichskommissariat Niederlande, Hitler’s occupation regime that controlled the Netherlands between 1940 and 1945. They’re both protected and pursued by scenery.

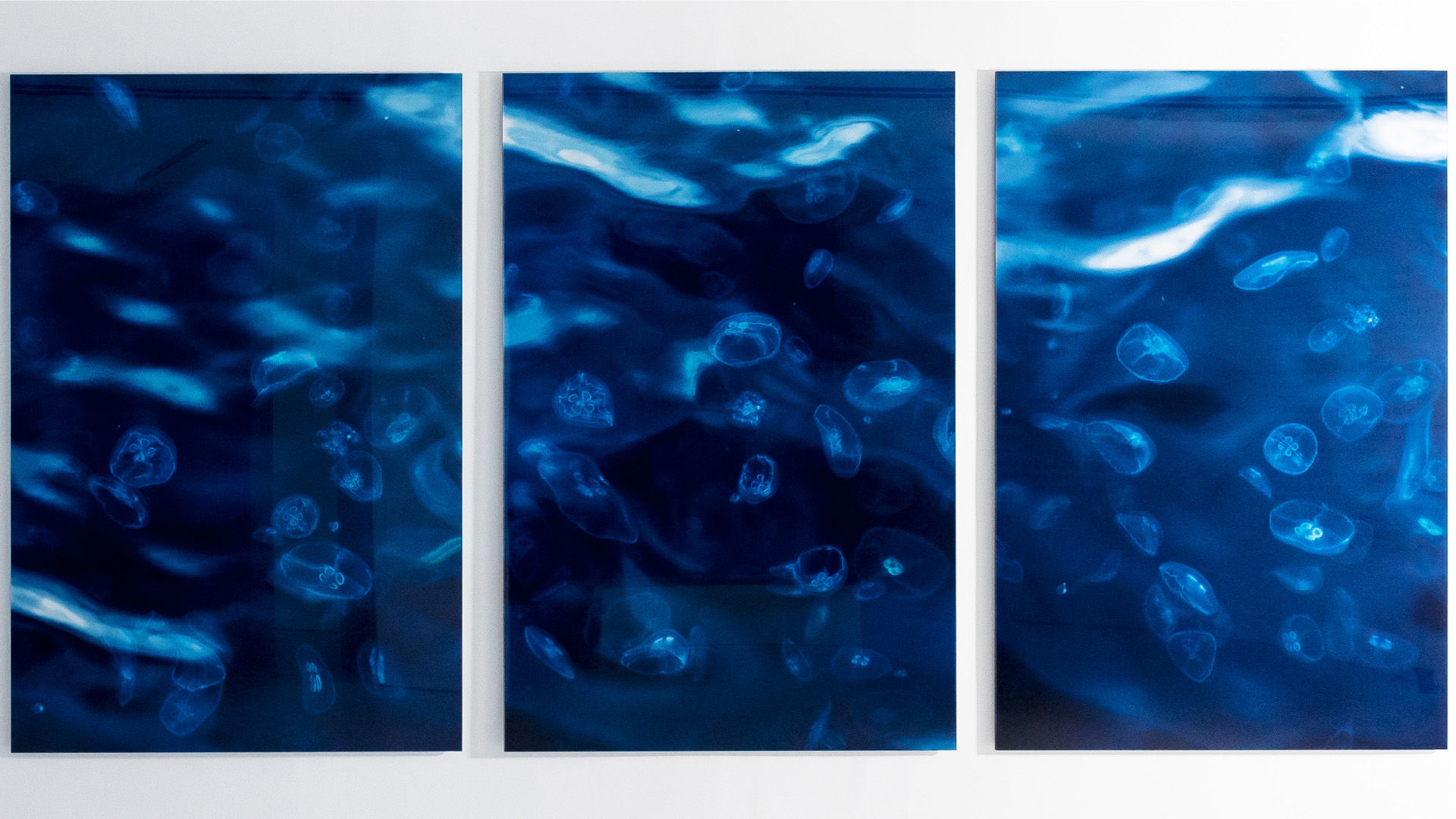

Ellen Kooi, Schoten-Waterlelies, 2014.

110 x 163 cm. Fuji Crystal archive print, diasec dibond.

Kooi studied art at Amsterdam’s Rijksakademie but her image-making suggests a second education in film. In Overveen-vogelmeer (2013) a wild European bison glares a woman lying in the front of the image, and Kooi uses a low-point-of-view, a trademark of Hitchcock, to capture their encounter. The image’s intensity emanates from not seeing the woman’s face. Instead we inhabit the anticipatory point of view of a film camera and our gaze surveils nature’s fate. Like Hitchcock, Kooi employs the camera to forge fantasies and record realities in the same instance.

But these aren’t fantastical images of fashion shoots. On the contrary her work in our season of pandemic panic proved prophetic. “There isn’t a big difference between today’s lockdowns and the emptiness of the past,” Kooi told me recently, in a Zoom interview.

“If I go to fields and lakes it’s always in the early hours of the day. They’re usually empty when I take a walk. It seems like if I look at my own work, they’re a forecast of how life is now. This is also what I’ve heard from other people. One friend said: ‘Wow, you’ve forecasted this emptiness!’ I think that’s a recognition of how I relate to landscapes and what I recognise in them.”

Kooi uses landscapes, she told me, “as a means of telling something else about those who populate them.” Her figures, she added, “are distancing in a natural way. I like the language of bodies and how people relate to each other. You can learn a lot of things about people in the way they choreograph their bodies.” In Velsen-slootmist (2003) and Menaldum Mensen (2004) her bland, clean-cut figures both cohabitate and self-distance in their landscapes, captured at dawn and under fogs.

Ellen Kooi, Menaldum-Mensen, 2004.

85 x 188 cm. Fuji Crystal archive print, diasec dibond.

As social distancing measures transformed life Kooi noticed how the Dutch government attempted to choreograph human distance much in the same way she does in these works. “It is of course much more obvious indoors,” she says. “I see people moving around in stores in a way that reminds of me of dance.”

She was wrestling with a new body of work when the outbreak began. “It was a difficult time,” she says. “I was working outside and I felt I was doing something illegal. Another difficulty concerned my models. I was afraid to infect them. My models were already stressed because of the pandemic, and by asking them to change this or that about their hair or postures, I feared stressing them further.”

But landscapes without humans don’t excite her. “Drones don’t offer the most interesting point of view. I like to interpret how a person relates to a landscape. In drone views people are too small and you can’t relate to them.” She paused a moment and considered my Zoom background. “I’m interested in composition and form, in choreography and psychology,” she said. “A protagonist’s reaction to her landscape—that’s the story I want to tell.”

ABOUT THE WRITER

Kaya Genç is a contributor to The New York Review of Booksand the author of Under the Shadow (I.B. Tauris), a ‘fascinating and informative compilation that represents both investigative and literary journalism at their finest’ according to Publishers Weekly. The Economist called Under the Shadow a ‘refreshingly balanced’ book whose author ‘has announced himself as a voice to be listened to’. The Atlanticpicked Kaya’s writings for the magazine’s ‘best works of journalism in 2014’ list. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Nation, The Paris Review, The Times Literary Supplement and The London Review of Books. Kaya holds a Ph.D. in English Literature. He is a critic for Artforum, and he gave lectures at venues including the Royal Anthropological Institute and appeared live on flagship programmes including Midday on WNYC and BBC’s Start the Week.