Blog

Rest in Neon Keith Sonnier!

20 August 2020 Thu

Keith Sonnier, who mastered his materials and self-expression to such an extent as to contribute to the definition of post-minimalist and process-oriented art movements with his works, Keith Sonnier whose colorful lights will never go out, passed away on July 18 at the age of 78. Our task is to commemorate once again this accomplished artist, who was also included in the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection with one of his works, by looking at his practice.

DENİZ CAN

denizdcan@me.com

Included in the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection with his work titled Ballroom Chandelier Installation, which was completed in 2007, Sonnier uses neon as a material. Sonnier uses neon, most often used commercially, with a brand new sensitivity in his works that intensely stimulate the senses. Today we come across thousands of neon artifacts that construct sentences, point, warn, flash, draw attention, draw boundaries. What's more, neons greet us as cheap signs that we come across as we turn every corner, above and below the buildings. In the 60s, Sonnier uses the neon material to make sculptures in a way that we cannot easily come across today, and these works reached the present day without losing their originality. Similar to Sonnier, artists such as Dan Flavin (minimalism) and Joseph Kosuth also create sculptures using lighting elements, fluorescent, and neon. Artists such as François Morellet (1926-2016) and later Iván Navarro (b.1972), Brigitte Kowanz (b.1957), Doug Aitken (b.1968) and Airan Kang (b.1960) are also included in the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection, making use of light as a material. In this sense, it is no coincidence that Arte Povera, which started as an Italian art movement and went on to influence the whole world at parallel times, directed the material preferences of the mono-ha group in Japan and the anti-form trend in America towards materials other than traditional ones. Artists who are involved in these movements that run parallel to each other often challenge the values of a commercial art world with their material choices. On the other hand, they get rid of the limitations of traditional materials and obtain a new and wide experimental field of their own.

Portrait of the artist courtesy of Caterina Verde.

Published by Ertuğ & Kocabıyık in 2011, the publication on the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection dedicates a section to light art in the first volume. Melanie Franke defines Sonnier as a pioneer of light art who has devoted his oeuvre to this phenomenon. According to Franke, Sonnier was enchanted by the effect of neon light and in the course of his artistic explorations always staged it with various materials and situations (2011, p. 80). Witnessing the beginning of an era when divested or shining, mass production or industrial materials were included in the arts, Keith Sonnier embodies the energy of light and electricity using neon. The works that stimulate our sensual perception due to the nature of the post-minimalism movement they contribute to, invite us to be involved in the process as opposed to being closed circuit works in themselves. Unlike the Greek sculpture placed on a pedestal, Sonnier's sculptures suggest that black cables and sockets as well as glowing lights can contribute to perfection, without idealizing or imitating nature and body. These works, which turn into darkness without electrical energy, make visible the relationship between electricity and material, which we are so accustomed to today, and the nature of the vibrating, heating, living work.

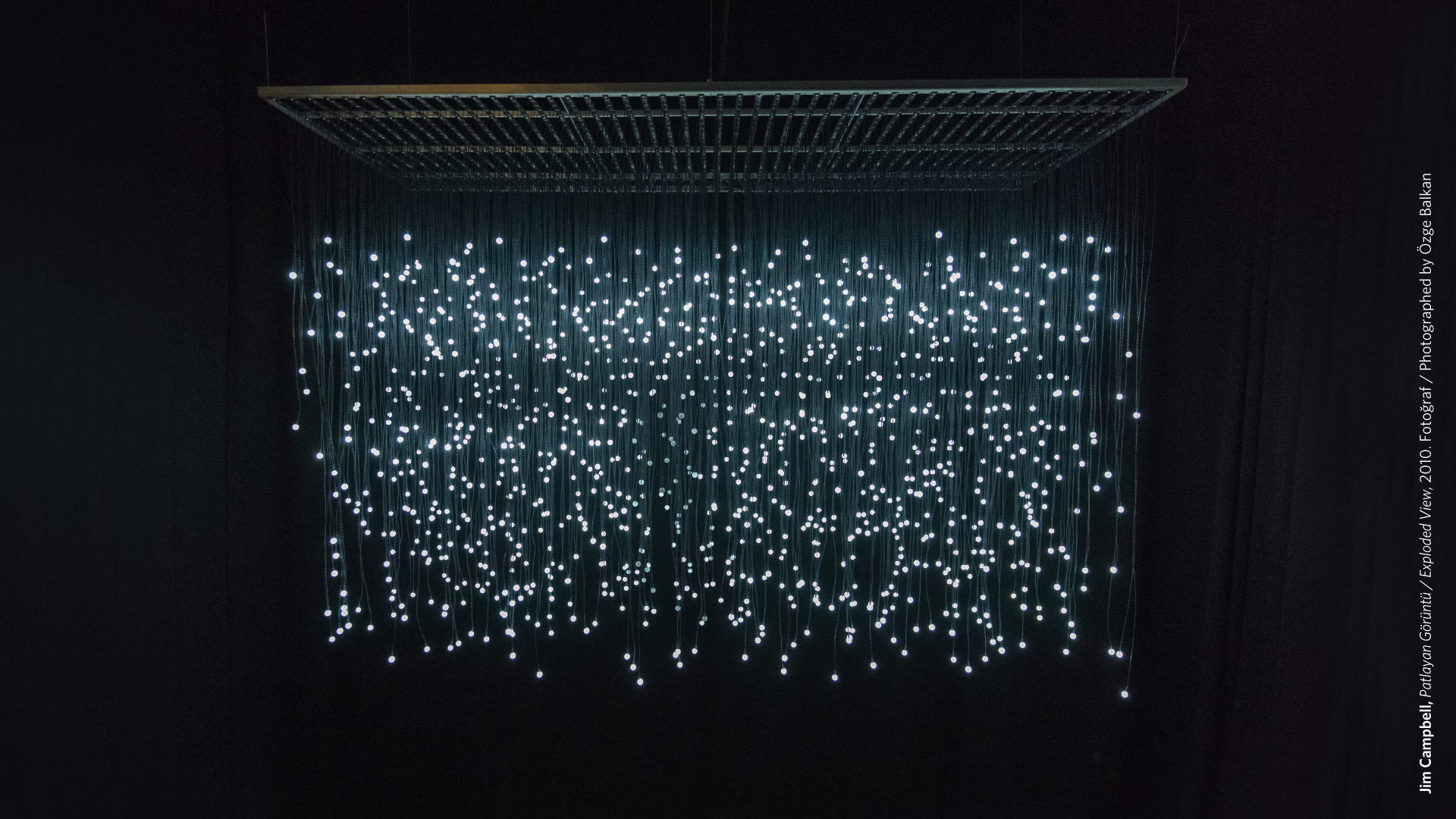

On the Ceiling: Keith Sonnier, Ballroom Chandelier, 2007.

Glass tubes with argon and neon, cable, transformer, 100 x 600 x 100 cm.

Looking at Sonnier's nearly 60 years of artistic practice, it is possible to read through his works, which do not accept limits, constantly experimenting and innovating. Freed from the impositions of traditional material, paint, canvas and stone, the artist gets rid of the boundaries of industrial materials through neon and the artist's production experiences a transformation that will last for years. Ballroom Chandelier Installation (2007) appears at first glance as a chandelier as the title indicates. But the work goes far beyond being a ceiling lighting fixture, it turns into a form in its own right and almost a living work of art. The electrical wiring hidden under the walls meet with cables and neon on the surface and remind viewers of its existence. Almost the whole building starts to breathe. The light emanating from the statue blends into the architecture that surrounds it and occupies the space. Curved neons are reminiscent of light beams flying around playing games in the air. Rather than sculptures placed on the space and left alone, Sonnier's sculptures reflect the process and movement. It is evident from every state that these works are born out of a serious design process in direct proportion to their simplicity and their impact. The distant footsteps of abstraction and minimalism are heard in the background. Nevertheless, these sounds gradually disappear in the shadow of the audience connecting with the works and organic forms that connect with nature. Personal experiences and observations turn into striking arrangements. In her text, Franke points to the social and historic features of the chandelier. According to the author, a hierarchically composed symbol of power is replaced by a pluralist diversity of voices, which distance themselves autonomously from the space and at the same time cause it to vibrate as a symbol of luminous energy (2011, p. 81).

Keith Sonnier, Ballroom Chandelier, 2007.

Glass tubes with argon and neon, cable, transformer, 100 x 600 x 100 cm.

It is almost a paradox for an artist who deals with light and dark, light and colors arising from light to produce a "chandelier"; or maybe a return to self, a mischievous look at himself. Sonnier must have accepted this paradox as a suitable idea for a series, different “chandeliers” decorate different spaces over time. According to Franke, for Sonnier the lamp became the medium with which light could be explored as a form of energy in economic and social systems and questions relating to the boundaries between art, design and recycling could be renegotiated (2011, p. 81). Unlike the Ba-o-Ba series that Sonnier started to produce in the late 70s, for example, the chandeliers draw attention to the material of neon alone and not the combination of glass, neon, and other materials. However, according to the artist, the shaping of the neon in the chandeliers (gestural) establishes a relationship with the past works of the artist, in which light is used in rings. On this occasion, we also have the opportunity to see how Keith Sonnier's relationship with light has progressed over time. Over the course of his practice, Sonnier shapes light and neon, sometimes in a geometric arrangement and sometimes in free forms, with a contemporary look at his past works. With the magic of light, Sonnier, who impacted us in spaces of different scales—in a small room, or in a gigantic public space—by shaping light into different shapes. Hoping that his neons will keep on shining.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Deniz Can joined the creative industries in 2011 in Izmir as the program director of KKSM. She realized the first Art Route events in which exhibitions on a monthly-created road map are discussed during visits with the support of local administrations, cultural institutions, and universities. The event series planted the seeds for the experiential art initiative that she co-founded. Can, who continues her works focused on arts and visitor experience in Istanbul, Izmir and abroad, moved to Istanbul to continue her institutional curatorial practice as an independent curator. She carries forward her academic writing skills professionally following the education she received in American Collegiate Institute, Economy Department in Koç University and Masters in Cultural Management at Istanbul Bilgi University