Blog

Some notes on an expansive view of Sol LeWitt in three parts

27 August 2025 Wed

In the third and final part of the series, Esra Plümer Bardak explores the breadth of Sol LeWitt’s artistic productions through his experimentation with diverse techniques and materials, as well as his distinctive, thought driven approach to artmaking. Central to this discussion is LeWitt’s concept of the “avid viewer”, an engaged observer whose interaction with the artwork is essential to its meaning and experience.

PART THREE: Versatility in Sol LeWitt's practice

As one the most significant American artists of the post-war era, Sol LeWitt is considered the frontrunner of 1960s minimalist and system-based conceptual art practices where the emphasis is placed on ideas over end results. LeWitt’s structures and wall drawings dominated his reception for most of his career, becoming the two pillars that best demonstrated the vital elements of his artistic ideology and practice. These seminal works, as discussed in Part One, signal on the one hand, in the anti-aesthetic tradition of Marcel Duchamp, a detachment from the primacy of material presence, allocating precedence to the idea or the thought process, as well as a return to a mechanical form of production embodied as a desire to evoke clarity and comprehension through systems of thought. 1 However, LeWitt returned to the materiality of colour and painting in printmaking in the 1970s, culminating his systems-based methodology with the inherent technical and mechanical properties of the medium.

These works are, as discussed in Part Two, alluringly colourful and in stark contrast to his paired back monochromatic structures and systems-based drawings from the 1960s. LeWittt’s use of printmaking as well as other media draw inspiration from a number of sources, cross pollinating a series of permutations across a vocabulary of geometrical forms, lines, bands, swingles, and colours, merging both optical and mental experiences.

In the 1980s, the year Sol LeWitt moved to Italy, he had also begun to work in ink washes, combining the four colours that form his vocabulary: black, yellow, red, and blue into a range of hues he used in later examples such as Wall Drawing #766 (1994). At this time, LeWitt would have had access to Trecento and Quattrocento frescoes such as the Arena Chapel in Padua and architecture, such as Alberti’s geometric façade of Santa Maria Novella, for example, which was among bands of lines of different hues he found most compelling. 2 LeWitt acknowledges the influence of Italian architecture and these painted walls on his own drawings, and goes so far as to write in a letter to Andrea Miller-Keller, curator at the Wadsworth Atheneum that in his work he strives “to produce something [he] would not be ashamed to show Giotto.” 3 In light of this, LeWitt’s wall drawings for the 2nd Istanbul Biennale in 1989, the isometric heptagonal shapes adorning the Sülemaniye Madrasa can be read to be more an extension of LeWitt’s admiration for the mural and façades of Italian architecture and ‘masters’ of art history, rather than a nod to Islamic art.

Importantly, the isometric method of perspective seen in Drawing #766, Distorted Cubes (2002) and the series of prints Isometric Figures in Five and Six Colours (2000-2002), is not meant to suggest any kind of spatial recession or architectural illusionism. Here, “the dimensions of the cubes reflect the boxes of the grid in which they are situated. The grid, a fundamental tool that LeWitt has used to organize his walls in most of his drawings, is distorted: stretched and pulled in order to create this irregular pattern of rectangles. The cubes inside the grid stretch or pull in response to the distortion of the squares.” 4

Reminiscent of Kelly’s objective with his colour reliefs (“I no longer wanted to depict space, but to make a work that existed in literal space”) LeWitt’s works use linear perspective to indicate volume, without compromising the flatness of the wall or the surface of the paper. LeWitt later continued exploring floating isometric shapes in many of his ink wash wall drawings. Wall Drawing 415, first conceived in 1993, is one of the earliest examples of these drawings, depicting two floating cubes. LeWitt drafts them isometrically, a technique in which all angles of the form appear equal, suggesting volume but not the illusion of depth. 5

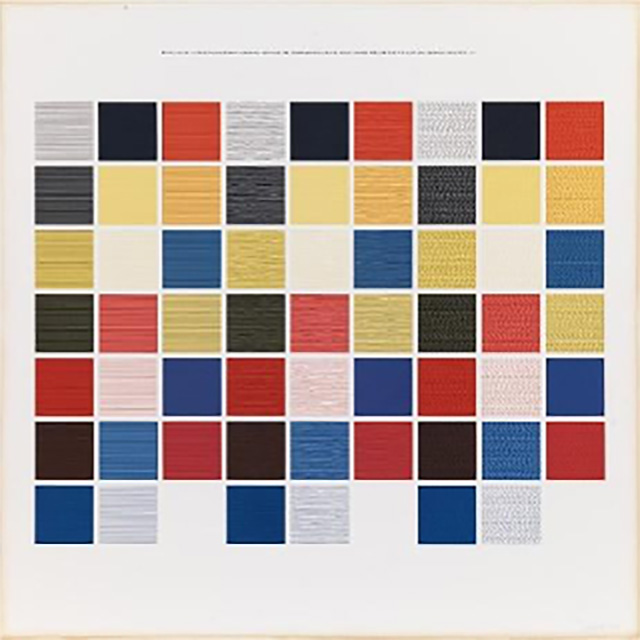

Sol LeWitt, Lines and Colors. Straight, not Straight and Broken Lines using all Combinations of Black, White, Yellow, Red and Blue for Lines and Intervals., 1977, screenprint on paper, 76.2 x 76.2 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing 766, 1994, Colour ink wash. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

In these instructions, there are codes such as the coating of colours playing with the endless spectrum of colour possibilities. Like Kelly’s chance combinations, where any colour goes, LeWitt’s use of primary colours was another way of striping art down to its bare essentials, with colour becoming another governing idea behind the form in a systematic manner.

The multiple modular method employed by Sol LeWitt, executed through geometrical shapes, different types of lines as well as colour, exploring different permutations through a method of repetition and rotation. These permutations, and the methodical approach in making exemplifies the reconciliation and contradiction between what is perceived by sight and what is understood by mind. This peripatetic mode of thinking, producing and viewing is most apparent in LeWitt’s series of prints, “where one not only must see one side of the print marks in total but often from multiple vantage points and in close up, from each side and even from behind.” 6 Commenting further on the prints, David Areford observes that, “What at first glance might appear strictly systematic or repetitive revealed itself to be intensely human, the product of problem-solving, focused mark-making, and often time-consuming physical and mental labour.” 7 Areford situates LeWitt’s prints within the broader context of his serial-, system-, and rule-based approach to artmaking. The specific processes of print media were perfectly suited for LeWitt’s particular brand of conceptual art, in which the idea is literally handed over to a machine that makes the art.

LeWitt points out that the conceptual proposals are simple ideas that do not require logical explanations. It is important to understand that even though Conceptual Art does not express rational judgements, it is not an expression of intellectual aridity as emphasized in Sentences on Conceptual Art (1969). LeWitt begins his text with the notion of “conceptual artists [being] mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.” 8 He carries on to explain that since rational judgements repeat rational judgements, propositions of illogical judgements lead to new experiences, which could be observed as the artistic objective of conceptualism. The writings of LeWitt introduce Conceptual Art as an intuitive procedure that is involved with all types of mental processes rather than being illustrative of specific theories and that has no purpose.

For LeWitt an ‘avid viewer’ would seek to decipher the work’s original idea along with the process that went into the making. Knowing the method or system behind the art is indexical to the optical experience. Here, conceptual art for Sol Lewitt becomes operational, or computational akin to programming or coding, and the audience becomes a user deciphering the program. This is not to say that the human aspect is removed from either the production process or reception. When asked about viewers understanding the process of the work, LeWitt commented “It isn’t important at all, it’s only important to me…. All you do is see it”.

While the MoMA exhibition discussed in Part Two, helped cement LeWitt as a major contributor to American modernism, it also received mixed reviews on the progressive or unique nature of the works, together with a confusion around the seeming contradictions between the artist’s intention and the works; “They seem remarkably visual for works many have held for nonvisual, more often the form, the visualization, than the idea.” 9 Flynn’s reading highlights a common misconception tied to conceptual art, that what we look at does not matter, or matters less, somehow.

Ultimately, it’s still about looking. However, there are several levels to looking. For a viewer, these prints as well as LeWitt’s entire oeuvre can be puzzling. However, to the avid viewer, these works can be puzzles, a reference to Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, a dazzling choreographic performance, a Baroque compositional masterpiece or a system based on the corner of a Quattrocento architectural façade… The spaces of discovery and possibilities in all their variations are endless.

Scholarship, especially in the past decade have opened the doors and viewers eyes to understanding household artists on a grand scheme. In line with this, Sol LeWitt’s work has been discussed in depth, not only within the scope of his most visible and well-known wall drawings, or structures that are also in public space, but are inclusive of a wider media of production which he employed. Works on paper, prints, photography as well as the “unproductive” or “failed” projects show a more expanded view of Sol LeWitt and his ideas as artist that worked, and as Anna Lovatt points out, and sometimes “malfunctioned”, as machine. 10

In fact, when LeWitt first introduced acrylics in his wall drawings in 1969, specifically Wall Drawing #14, he included a geometrically figure a square on the floor, demonstrating the “elasticity” of the term “wall drawing” in these early years. LeWitt incorporated acrylic paint and colour from 1975 onwards, “testing the limits of pictoriality” referencing the history of painting, including the Italian masters, also modern painting. In understanding Sol LeWitt, we must look at a “plural LeWitt”, as David Areford has advocated, a more expansive view of the artist and his practice, one that fully embraces the multiple mediums he pursued and the sometimes difficult and contradictory aspects of his conceptual art.

Returning to Baldessari mentioned in Part One, and his playful inquiry into production, reproduction and looking, we must question the takeaway from the caption (together with much of LeWitt’s writing) that declares that conceptual works are in fact ‘not to be looked at’ but thought of, as Donald Kuspik has described in 1975, “epitomising the look of thought, requiring an intellectual response rather than physical apprehension. One does not so much see them, but think about them.” 11 However, the alluring nature of Sol LeWitt’s prints relinquish the viewers senses over to an array of shapes and colours, which perhaps invites us to reconsider this dichotomy. Victor Burgin’s reflections on Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigationsmay be helpful here, where he explores how we can simultaneously look at something and think about it. 12 Entering the realm of the ‘virtual’, the image for Burgin is neither a material entity nor simply an optical event. Thus, the dichotomy between form (material) and content (idea), which Baldessari’s work raises issue with, as Godfrey point out, is a “false dichotomy” that feeds the rudimentary definitions and parameters of LeWitt as he has come to be known, in turn obstructing the understanding of LeWitt’s practice as a whole; an oeuvre full of contradictions, errors and all.

The prints in the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection are significant in recognising and looking at Sol LeWitt not only as an avid viewer but in demonstrating how they contribute to a more expanded interpretation of the artist, his oeuvre and legacy.

1- Hal Foster in The Return of the Real ties this to a “return to the earlier conceptualism of Duchamp and Dada,” as quoted in Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Art (2002) p. 386. See Chapter 1. In Hal Foster, Return of the Real (MIT Press, 1997) pp. 1-35. However, LeWitt has often refused this direct association in interviews. See “Sol LeWitt in Conversation” in Sol LeWitt Structures 1965-2006, ed. Nicholas Baume. (New York: Public Art Fund and New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011). Pp. 110.

2- David Areford, “Sol LeWitt: Thinking Through Prints”. September 23, 2022. New Britain Museum of American Art. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ZafqybdEUM&t=3438s&ab_channel=NewBritainMuseumofAmericanArt

3- Sol LeWitt and Andrea Miller-Keller. 1981-1983. Sol LeWitt Critical Texts, AEIUO, Incontri Internazionali D'Arte, Rome, Italy, editing by Adachiara Zevi, 1995

4- Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing 766, 1994. Object Caption. MASS MoCA. Available at: https://app.cuseum.com/art/sol-lewitt-wall-drawing-766

5- Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing 415D, 1993. Object Caption. MASS MoCA. Available at: https://massmoca.org/event/walldrawing415d/

6- David Areford, “Sol LeWitt: Thinking Through Prints”. September 23, 2022.

7- David Areford, “Sol LeWitt: Thinking Through Prints”. September 23, 2022.

8- Sol LeWitt, “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” in Art in Theory 1900-2000 An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Massachusetts, Oxford, Victoria: Blackwell Publishing, 2002). p. 849.

9- In the same article, the critic writes; “LeWitt’s art has too many of its own answers to constitute an alternative for anyone else, and (2) it can’t be a beginning, because it marks out a dead end.” Barbara Flynn, “Sol LeWitt: MoMA – The Museum of Modern Art”. Artforum. April 1978, Vol. 16, No. 8. Available at: https://www.artforum.com/events/sol-lewitt-12-230600/

10- Anna Lovatt, “LeWitt’s Malfunctioning Machines” in David S. Areford in conversation with Anna Lovatt, Veronica Roberts, and Kirsten Swenson. Online discussion presented by 192 Books and Paula Cooper Gallery. June 3, 2021. Available at: https://paulacoopergallery-studio.com/posts/locating-sol-lewitt

11- Donald B. Kuspit, "Sol LeWitt: The Look of Thought," Art in America (New York), September-October 1975, pp. 43 -49.

12- See key writings by Victor Burgin, Thinking Photography (1982), The End of Art Theory: Criticism and Postmodernity (1986), In/Different Spaces: Place and Memory in Visual Culture (1996), The Remembered Film (2004), Situational Aesthetics (2009), Parallel Texts: Interviews and Interventions About Art (2011).